'We've been sacked': the 1975 Whitlam government dismissal

For the first time in Australian history, a governor-general dismissed a prime minister and government. How did this constitutional crisis come about?

'Well may we say, "God save the Queen", because nothing will save the Governor-General.' This is one of the most famous lines ever uttered by an Australian politician. It marked an extraordinary moment in Australia's political and constitutional history – the dismissal of the Whitlam government on Remembrance Day 1975.

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam delivered his now iconic line as an off-the-cuff remark as he stood on the steps of Parliament House to hear the Governor-General's proclamation dissolving parliament. Read aloud by the Governor-General's Official Secretary, David Smith, it concluded with 'God save the Queen', prompting Whitlam's instantly famous response.

The Whitlam dismissal is the first and, so far, only time an Australian prime minister and their government has ever been dismissed.

Gough Whitlam on the steps of Parliament House after the dismissal speaking to the press and assembled crowds, 11 November 1975.

Photograph National Library of Australia

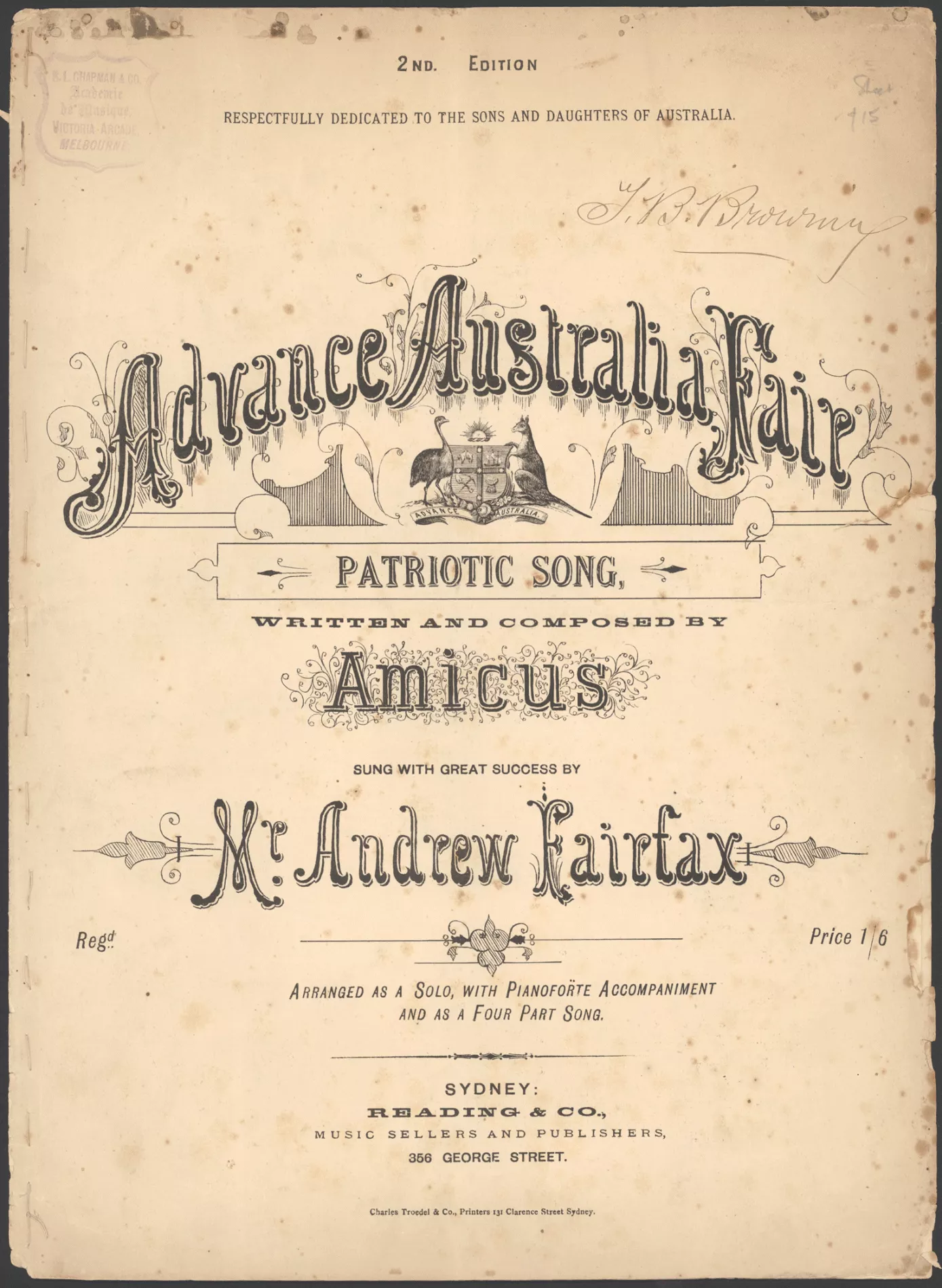

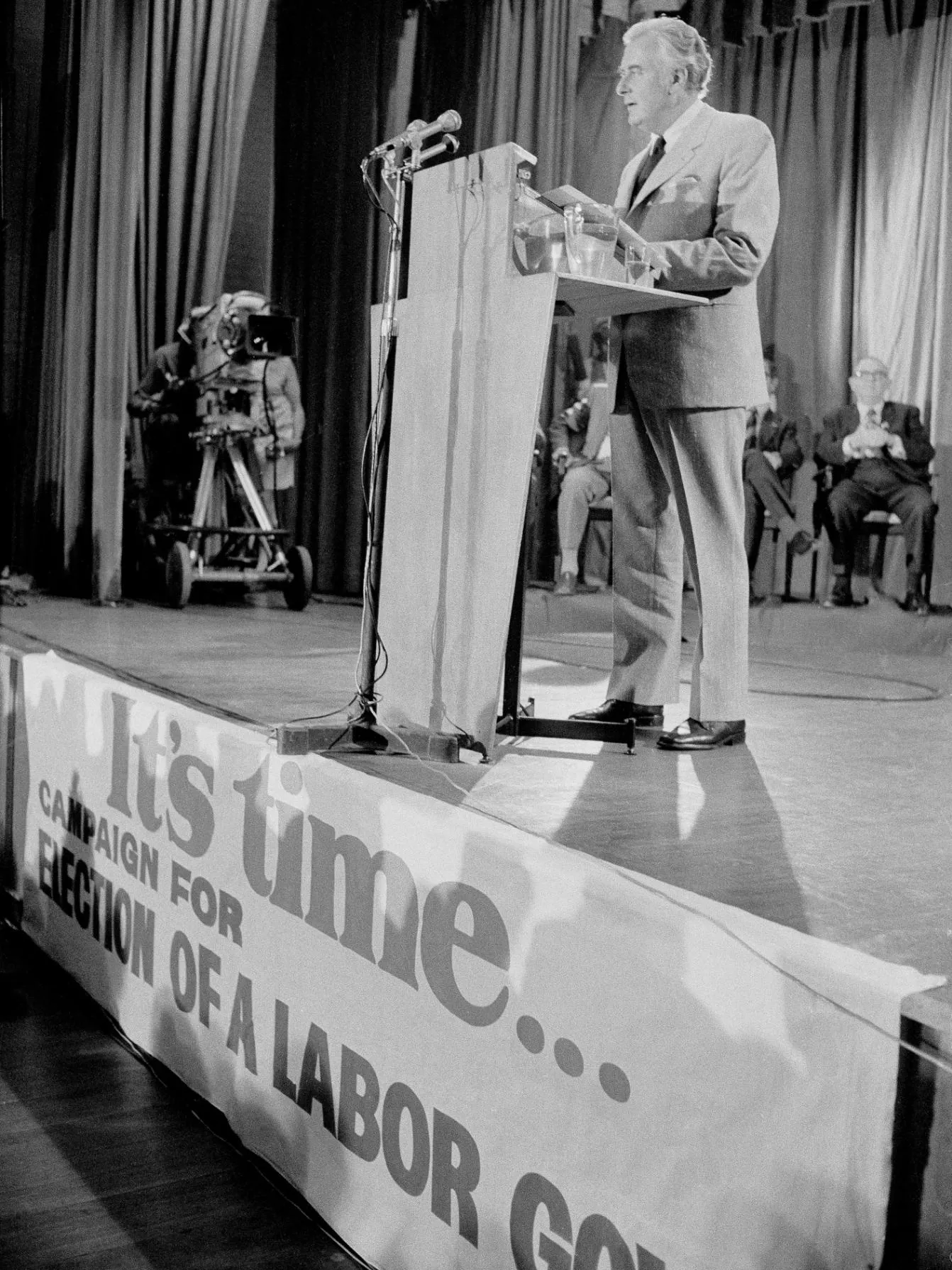

The Whitlam government is elected

For 23 years Australia had been governed by a Liberal–Country Party Coalition, but in 1972 the Australian Labor Party's rallying campaign message for change, 'It's Time', galvanised voters and saw Labor swept into power with its leader, Gough Whitlam, appointed prime minister.

Lack of control of the Senate

Despite having won the election, Labor found itself in a challenging position. It controlled the House of Representatives, but not the Senate. For almost three years, neither the government nor the Opposition enjoyed a clear majority in the Senate.

Turbulent times for Whitlam's Labor government

Political missteps, scandals and party issues plagued Whitlam's government, destabilising its political credibility and weakening its support in the electorate.

A double dissolution election in May 1974 reduced Labor's majority in the House of Representatives to just five, with both Labor and the Coalition tied on 29 in the Senate. In the wake of the election, Malcolm Fraser became the new leader of the Opposition.

In June 1975 Labor lost the (previously extremely safe) seat of Bass in Tasmania to the Liberals in a disastrous by-election, then endured the so-called 'loans affair'. When the Opposition finally gained a majority in the Senate in mid-1975, it had the means – and the determination – to force an election.

Blocking the supply of government money

On 15 October 1975, Malcolm Fraser announced he would use his Senate majority to block the Labor government's Budget by delaying passage of the supply bills until the government agreed to call an election.

- Malcolm Fraser

For his part, Whitlam also thought he had the authority of the Australian Constitution behind him: 'A government that continues to have a majority in the House of Representatives has a right to expect that it will govern'.

Both Fraser and Whitlam were relying on their own interpretations of Sections 53 and 57 of the Constitution concerning the Senate's power to block supply.

Deadlock

Neither Fraser nor Whitlam was willing to back down. Whitlam repeatedly sent the supply bills back to the Senate, needing just one senator to cross the floor in order to defeat Fraser's tactic. However, none did, and the deadlock dragged on for weeks. The government's money would soon run out.

The dismissal

On Tuesday 11 November 1975, Governor-General Sir John Kerr used his reserve powers to break the deadlock, dismissing Whitlam for refusing to resign or to advise an election after failing to obtain supply. The previous day, Kerr had obtained formal advice from Sir Garfield Barwick, Chief Justice of the High Court, that confirmed his right to dismiss the government.

It was a day of high drama from start to finish. That morning, Kerr and the Opposition Leader Malcolm Fraser spoke on the phone. Fraser claimed Kerr had asked him a series of hypothetical questions, including 'If commissioned as caretaker prime minister, can you guarantee to provide supply?' Fraser answered in the affirmative, and they arranged to meet at Government House later that day.

Meanwhile, Whitlam had also arranged to meet the Governor-General, but when he arrived at Government House, to his shock, Kerr handed him a letter terminating his commission and that of his government. When Whitlam shared the news with his chief advisers, he reportedly said, 'We've been sacked'.

Shortly after Whitlam left Government House, Kerr swore Fraser in as caretaker prime minister. Fraser returned to Parliament House and the supply bills were passed.

Fraser then stood in the House of Representatives and declared: 'Mr Speaker, this afternoon the Governor-General commissioned me to form a government until elections can be held.' The house erupted, and Fraser moved to close the session under shouts from Labor members of, 'Shame! Shame!'

Shortly afterwards, the Governor-General signed both the supply bills and a proclamation dissolving both houses of parliament and calling for an election on 13 December.

At around 4.40pm the Governor-General's Official Secretary, David Smith, with Whitlam looming over his shoulder, read out the proclamation on the front steps of Parliament House in front of thousands of protesters. Smith was drowned out by cries of 'We want Gough!'

Smith finished with the obligatory phrase 'God save the Queen!', and Whitlam stepped forward to address the fervent crowd: 'Ladies and gentleman, well may we say, "God save the Queen", because nothing will save the Governor-General.'

What happened after the dismissal?

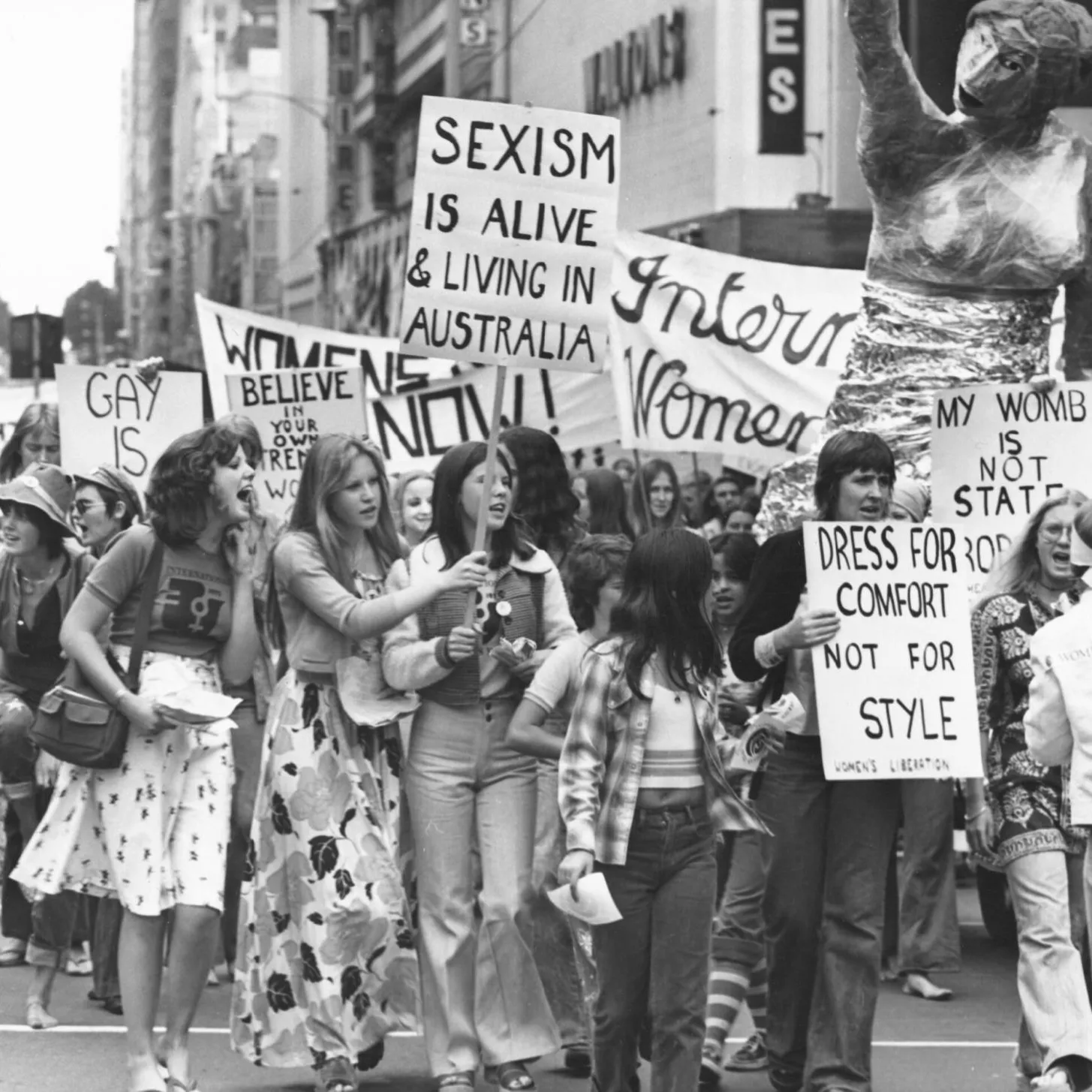

The December election campaign was divisive and saw high emotions on both sides.

Labor's campaign focused on diminishing Fraser's credibility, along with the dismissal and its perceived threat to democracy. Its slogan was 'Shame Fraser, shame'.

The Liberal and National Country parties' campaign stressed the high inflation and unemployment experienced under Labor, among other issues. The slogan 'Turn on the lights' telegraphed their view that the past three Whitlam years had been dark times.

Within just three hours of the polls closing, it was clear the coalition of Liberal and National Country parties had won, and Malcolm Fraser officially became Australia's 22nd prime minister.

Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, Governor-General Sir John Kerr and Deputy Prime Minister Doug Anthony leaving Government House after the swearing in of Malcolm Fraser's Cabinet, 1975.

Photograph NAA: A6180, 13/11/75/1

Why was the 1975 dismissal so controversial?

Fierce debate arose around the implications of the dismissal for the future of democracy in Australia. There were some who thought that it threatened the foundations of democracy because the governor-general had dismissed an elected minister and government. Others thought the dismissal was simply democracy at work: the seemingly irresolvable deadlock was broken, an election was called and a stable government was restored.

Could a government be dismissed again?

The provisions of the Australian Constitution that allowed Whitlam and his government to be dismissed have not been changed. Whether or not it's appropriate for the Senate to exercise its power to block supply of government money, it does retain that power and can use it to force an election. However, the Constitution doesn't specify whether a prime minister is required to call an election should that happen. This means a deadlock could occur again, and the governor-general still holds 'reserve powers' to break the deadlock by dismissing the prime minister and government.

What are the governor-general's 'reserve powers'?

A 'reserve power' is a discretionary power that a head of state or their representative may use without the approval of another section of the government. In Australia, the governor-general is the representative of the monarch and the 'reserve powers' arise from this designation. They are not laid out in the Constitution, but instead are guided by convention.

The governor-general's reserve powers include the right to appoint a prime minister in the case of an unclear election outcome, to dismiss a prime minister if they don't have a majority in the House of Representatives, to dismiss a prime minister or minister if they break the law, and to refuse a request from a prime minister to call an election.