Referenda and plebiscites – what's the difference?

- DateFri, 21 Aug 2015

There is often talk in the media about referenda and plebiscites. What is the difference between the two?

Basically, a referendum seeks to amend the Australian Constitution. It is the only way the Constitution can be changed – by a vote of the people. However, it requires a 'double majority' – a majority of all voters across the nation and a majority of the states. Voting in referenda is compulsory. Referenda are binding on the government.

A plebiscite is sometimes called an 'advisory referendum' because the government does not have to act upon its decision. Plebiscites do not deal with Constitutional questions but issues on which the government seeks approval to act, or not act. As with referenda, plebiscites require an enabling Act of Parliament. Whether or not a plebiscite is to be based on compulsory voting is determined by the enabling Act.

During the First World War, the Australian government held two plebiscites seeking public approval for conscription. Both failed. The only other Australia-wide plebiscite was held in 1977 to ascertain public opinion on the choice of a national song.

The Australian people have proven reluctant to support referenda: only eight out of 44 have been approved. (Note: Since this article was published, there was another referendum in 2023, which did not attract a 'yes' vote.)

The 1944 referendum

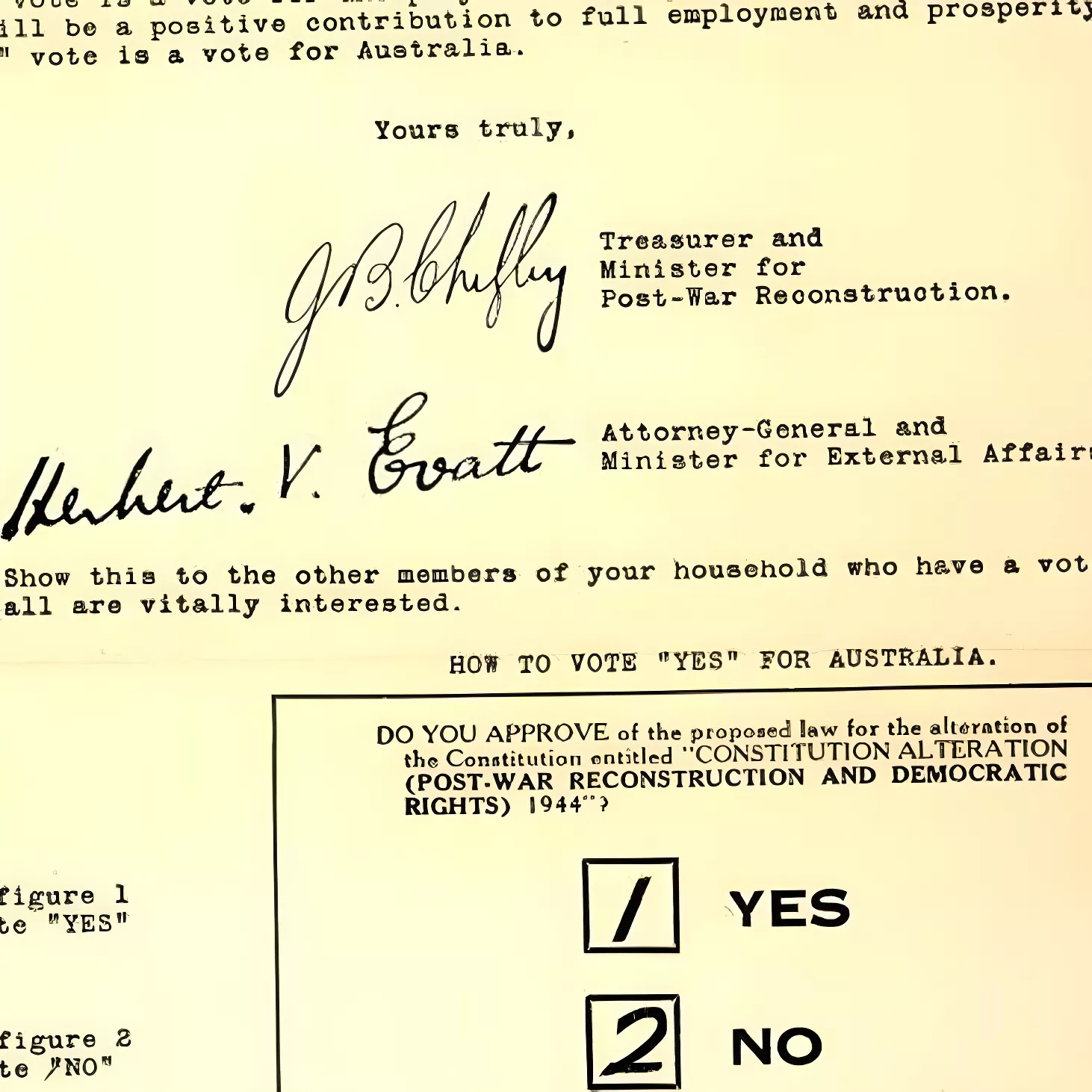

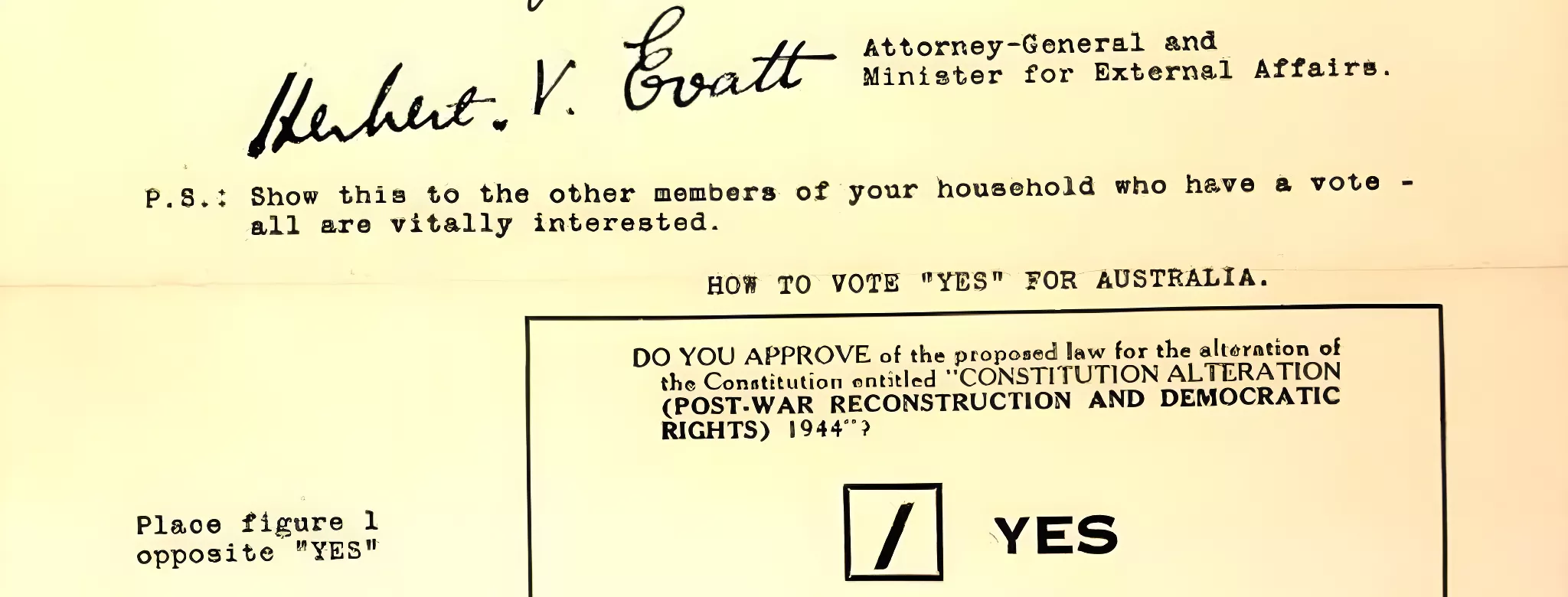

Seventy-one years ago, on 19 August 1944, the government headed by Prime Minister John Curtin sought approval for power to legislate on a wide variety of matters. The Second World War was ending, and it was clear the allies would win. The Curtin government wanted to extend its powers in the interests of national reconstruction after the war.

The phrasing of the questions in a referendum or plebiscite can be very important, perhaps even decisive. In 1944, the government put forward only one question but it had 14 components, including controversial areas about monopolies, combines, price controls, trusts and national health. The United Australia Party-Country Party Opposition, led by Arthur Fadden, saw elements of the question as dangerous to the social system. In parliament, Robert Menzies argued that some of the powers went 'beyond what a non-socialist programme of post-war reconstruction would require'.

The 1944 question was: 'Do you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled 'Constitution Alteration (Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights) 1944'?'

Among the 14 points was one seeking Commonwealth power to legislate on Indigenous issues, rather than control of Aboriginal affairs being with the states. One wonders whether this might have carried, had it been voted on separately.

The 1967 referendum

The 1944 referendum failed but 23 years later the Indigenous question was approved by the people. The 1967 referendum asked: 'Do you approve the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled 'An Act to alter the Constitution so as to omit certain words relating to the People of the Aboriginal Race in any State and so that Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the Population'?'

It is interesting that the question did not ask explicitly for Commonwealth power to legislate on Indigenous affairs but it was implicit: that was its intent and consequence. The 1967 referendum carried with a huge majority.

The phrasing of the question put to the people in both referenda and plebiscites is of great importance, but other factors also influence the likelihood of success or failure. The quality of the arguments for a 'yes' vote is important. But it could be argued that it is the strength of the campaign for a 'no' vote that is more crucial. No referendum has passed in which the Commonwealth opposition has opposed it.

Same-sex marriage?

Prime Minister Tony Abbott announced in 2015 that same-sex marriage would be resolved by a national plebiscite. Again, the phrasing of the question would have been interesting and influential to the outcome, as would be the strength of the case for a 'no' vote. (Note: The topic of same-sex marriage was eventually addressed through a successful voluntary postal vote in 2017, after which the Australian government legalised same-sex marriage.)

In Ireland, a referendum was held on this issue in May 2015. The Irish government wanted to add to the Irish Constitution the notion that 'marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex'. More than 60% voted 'yes'.

Perhaps a lesson from Australia's history of referenda and plebiscites is that it's best to frame the question in the simplest and clearest way possible. We can perhaps also learn from Ireland.