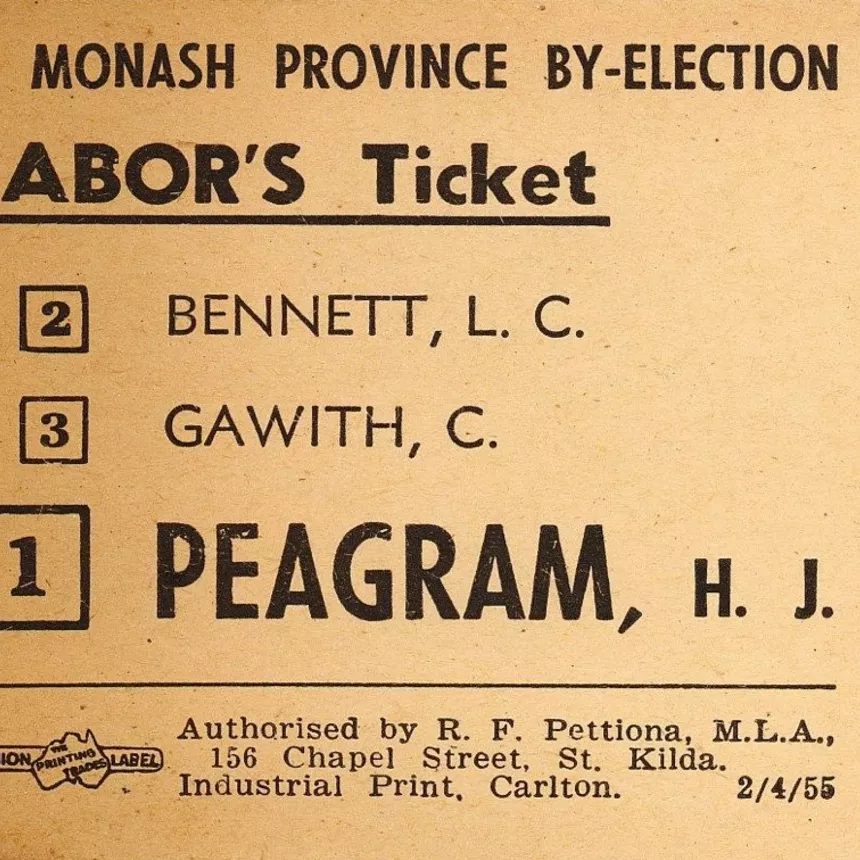

A horse’s tale: Bill, Bertie and Bairnsdale 303

- DateTue, 16 May 2017

Thousands of people attended the opening of Parliament House on 9 May 1927. Thousands of horses were also intrinsic to the event.

They pulled carriages and cannons, carried cops and troops and VIPs, and even danced to music on the Parliament House lawn. In 2016, one of these horses joined the Museum’s collection.

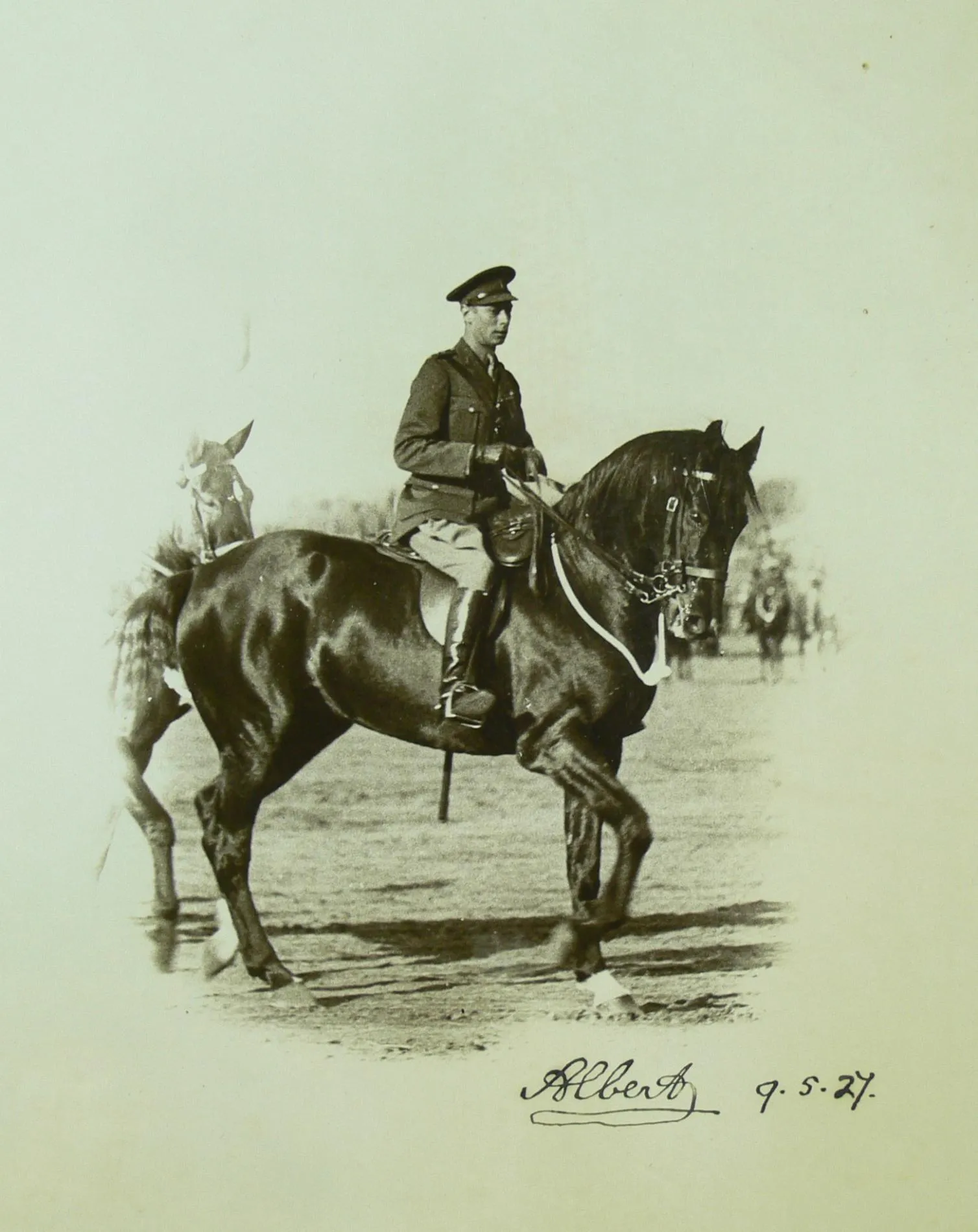

Alas, this horse is not real. Instead, he exists in three beautiful photographs that capture the shimmer of his silken coat and the gleam of his two white socks. The photos also show his rider: Albert, the Duke of York (Queen Elizabeth’s father). The horse’s name was Bill.

The photographs were donated by Barbara Walker of Inverell. Bill belonged to Barbara’s grandfather-in-law, Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Farr DSO. Lt-Col Farr was a First World War hero who was responsible for moving almost the entire public service from Melbourne to the nation’s new capital city, Canberra. According to family legend, Bill was loaned to the Duke of York because his calm temperament suited the Duke’s nervous equestrianism. But there was something intriguing about these photos.

Horses for courses

On 9 May 1927 a horse-drawn landau, complete with postilions wearing horsehair wigs, deposited the Duke and Duchess of York at the front steps of Parliament House. The Royal couple had arrived to open the building and the first sitting of federal Parliament in Canberra. After the ceremonies, the Duke had to take the salute at a troop review in what is now York Park, southeast of Parliament House. The two-hour review was to feature more than 2,000 troops, including Light Horsemen, and massed brass bands.

But the Duke couldn’t take the salute standing on his own legs. He had to ride a horse with the strength and stamina to handle the pressure. The horse also had to be very calm, because the saluting Duke would be holding the reins in one hand. These requirements were a big ask of an animal whose instinctive response to loud or scary situations is to flee.

Some 250 police horses were considered for the Duke. Only one made the grade: ‘a big, black mare, of magnificent appearance’, reported Brisbane’s Daily Standard on 6 May, ‘known officially only by a number – “303.”’ She was from Bairnsdale, Victoria, and usually ridden by a Constable Edgar. The Daily Standard continued:

Sydney’s Daily Guardian of 10 May even published a portrait of 303 – who was hastily re-named Black Bess. But her fame was fleeting. The newspaper revealed:

So this explains why, in our photos, the horse carrying the Duke is not the jet-black police horse, but Lt-Col Farr’s white-socked Bill. One photo shows the pair alongside another, solid-coloured horse ridden by the Governor-General, Lord Stonehaven. Was this Black Bess? One thing is certain: on 9 May 1927, Bill was not a rocking horse.

Bill seems unhappy with the situation.

Image: Museum of Australian Democracy Collection

Things get exciting

The first photo (above), taken at Parliament House, shows the Duke of York having just mounted and sorting himself out. Bill’s pinned ears and clenched jaw suggest he’s unhappy about the unfamiliar weight on his back. In the next photo (below), Bill is extremely alert. Something unusual has captured his attention – or he’s looking for a getaway. Lord Stonehaven, an experienced horseman, appears to be giving the Duke some tips.

The G–G appears to be giving the Duke some tips.

Image: Museum of Australian Democracy Collection

In the last photo, taken in what is now York Park, the Duke looks very nervous. He is perching rather than riding, and holding the reins high and tight. Perhaps he was trying to hold Bill back; if so, Bill’s Pelham bit (a contraption that intensifies the bit’s ‘braking’ action) is bottling up him up. Perhaps this is why the horse has coiled into a shiny muscular spring.

The Duke of York riding Bill.

Image: Australian Museum of Democracy Collection

What happened next? The Age of 10 May reported:

Poor Bertie. In the morning’s ceremonies he had fought off his stammer to deliver two important speeches scrutinised by the nation. Now he literally had his hands full with a high-spirited, high-powered animal with a mind of his own.

Poor Bill. The fluttering pennants and flashing bayonets startled at all angles. The blaring bugles and thumping brass bands sent strange vibrations through the earth and air. Bill pulled and bounced and flung his rider about. But those weights on his mouth only got harder and heavier.

The Herald of 9 May reported that the Duke ‘arrived on a bay, which began rearing as the party rode up the line for inspection.’ One spectator, Hilda Abbott (the wife of Northern Territory Administrator Charles Abbott), recalled ‘the Duchess looked anxious and her face had flushed as the horse had pranced about’.

An elegant solution

The troop review was a pageant to inspire loyalty and pride in the nation and the British Empire. In front of hundreds of cameras and thousands of people, the Duke had to be dignified and controlled. A lot of men at the troop review had fought a war in the name of his father, George V. To fall off his horse was unthinkable.

The Duke was flanked by Lord Cavan, the Governor-General, the three Defence Force Chiefs and twenty Light Horsemen. Dressed in khaki and surrounded by horses, he was difficult to distinguish from afar. The Duke swapped to Black Bess and the Governor-General mounted Lord Cavan’s horse. Most spectators did not notice the change. At the saluting base, Black Bess stood like a statue.

And Bill? The Daily Guardian reported that Lord Cavan ‘had a bad spin on [the] mettlesome bay charger, which insisted on doing the Charleston’. The Earl had broken his ankle in a riding accident just five months earlier but, the newspaper added admiringly, he ‘handled his mount like the Irishman he is.’

These small moments of high drama reveal much about human anxieties: the need for the ceremonies to go perfectly; for Royalty to appear infallible. But we often forget the experiences of the other important players hiding in plain sight. History is full of animals, but relatively few are remembered as individuals in their own right. And human memories are not always reliable. This is why these photographs hold such magic. Although Bill is long gone, he expresses his thoughts and feelings in his eloquent body language captured here, crystal-clear, for anyone who cares to interpret it.