A plebiscite milestone: 100 years on from the 1917 conscription debates

- DateWed, 20 Dec 2017

20 December 2017 marks the centenary of Australia’s second plebiscite on conscription.

Along with South Africa and India, Australia was the only participant in the First World War not to introduce conscription. Australia had compulsory military training for men aged 18 to 60 since 1911 but this did not extend to overseas service.

Reliance on volunteers for the European theatre soon created problems, as the numbers willing to serve overseas did not match the requirements of the British government. In 1917, for instance, the British requested an additional Australian army division and the Australian government was finding it impossible to raise the 7,000 men per month that this entailed.

The First World War was a horrific war which claimed the lives of 11 million soldiers and seven million civilians, and left 20 million wounded.

In the public mind, by 1917 doubts about conscription and, to a lesser extent, about the war itself, were growing.

Of the 416,809 volunteer troops Australia sent overseas, 61,524 were eventually killed. Many more were wounded, physically and mentally.

The Australian Labor government led by Prime Minister William (Billy) Hughes could have tried to introduce conscription by parliamentary vote but the question of forcing young men to fight was so controversial in the electorates and in the parliament, with the Labor Party divided over it, that the government opted instead for a national plebiscite.

The first vote took place in October 1916 and, to the astonishment of the ‘yes’ advocates, was defeated. This was quite a serious blow to British war requirements and was perhaps Australia’s first experience of a ‘Brexit factor’: people voting against the expectations of the Establishment.

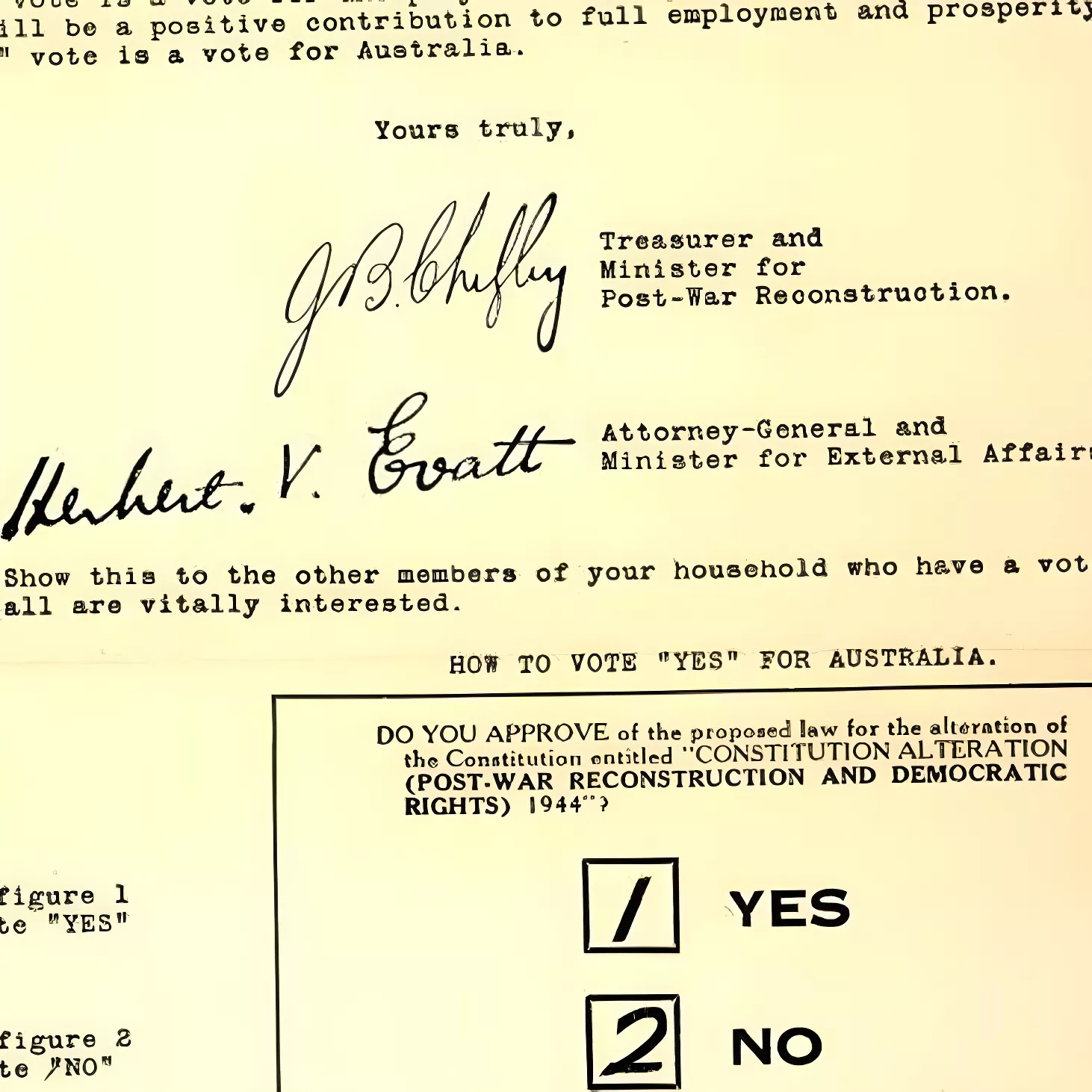

The first referendum asked: 'Are you in favour of the government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this war, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?'

The phrasing of the question in 1916 was hardly neutral – was it really a 'grave emergency' for Australians? – which makes the resultant negative vote all the more surprising. The vote was 1,160,033 'No' and 1,087,557 'Yes'.

With more deaths and casualties on the Western Front in 1917, and pressure from the British government for more support, Prime Minister Hughes, no longer in the Labor Party and now heading a Nationalist government, tried again. This time, the wording was even more loaded: 'Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth government for reinforcing the Australian Imperial Forces Overseas?'

How could any ‘patriotic’ Australian not support ‘reinforcing’ the troops who were already fighting overseas?

Yet they did, again. Only this time the ‘No’ vote was larger: 1,181,747 'No'; 1,015,159 'Yes'.

The ‘No’ vote was a tribute to the effectiveness of those who campaigned for it in 1916 and 1917, often under very adverse circumstances. Some opponents of conscription were gaoled, including John Curtin, who became Australia’s 14th Prime Minister in 1941.

The press was censored by the government and the ‘No’ campaigners portrayed as unpatriotic servants of the ‘Hun’. It was all very intense, passionate and polarised.

One can only speculate as to why the majority voted ‘No’ on two occasions but I suspect that the trade unions’ fear campaign about Australian workers being sent overseas and replaced by ‘cheap foreign labour’ was significant.

The trade unions and some women’s groups played important roles in the ‘No’ campaign. Women set up a Women’s Peace Army, which was highly effective.

Also, it is likely that many men and women of Irish Catholic background would have supported the ‘No’ campaign. The violent suppression of the Easter Uprising in Dublin in 1916 lingered in their consciousness and Melbourne’s Irish-born Archbishop, Daniel Mannix, supported the ‘No’ vote.

There were small groups of communists and anarchists who opposed the war itself, seeing it as an inter-imperialist conflict in which the working people had no vested interest. This was a minority view but given significance by the Russian revolution and the Bolshevik policy of withdrawing Russian troops from the conflict.

Surprisingly, the success of the anti-conscription movement did not translate into the defeat of the Nationalist government. Hughes’ Nationalists were returned at the federal election in 1917, following defeat in the first plebiscite, and returned again at the next election in 1919. It wasn’t until 1929 that a Labor government would come to power. It was headed by Prime Minister James Scullin, who had been a prominent opponent of conscription in 1916–1917.

A legacy of the 1916 and 1917 plebiscites is found in a cautious attitude to conscription for overseas service in Australian public opinion. The struggles of 1916–1917 were often alluded to during the late 1960s and early 1970s when public opinion came to oppose conscription for overseas service in Vietnam; though on this occasion, it eventually moved against the war itself.