Alfred Deakin and the Divine

- DateWed, 12 Mar 2014

Remember the days when people wrote with their bare hands? When there was a direct physical and mental connection between brain, body, ink and paper?

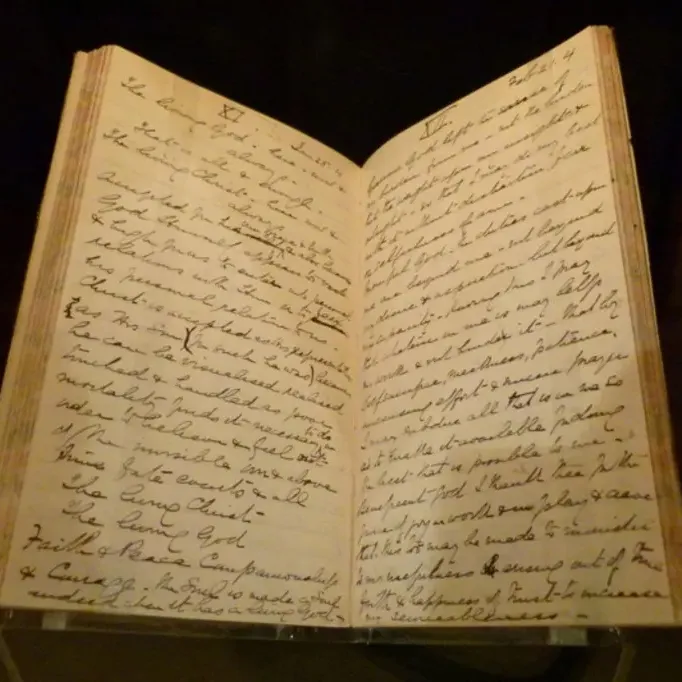

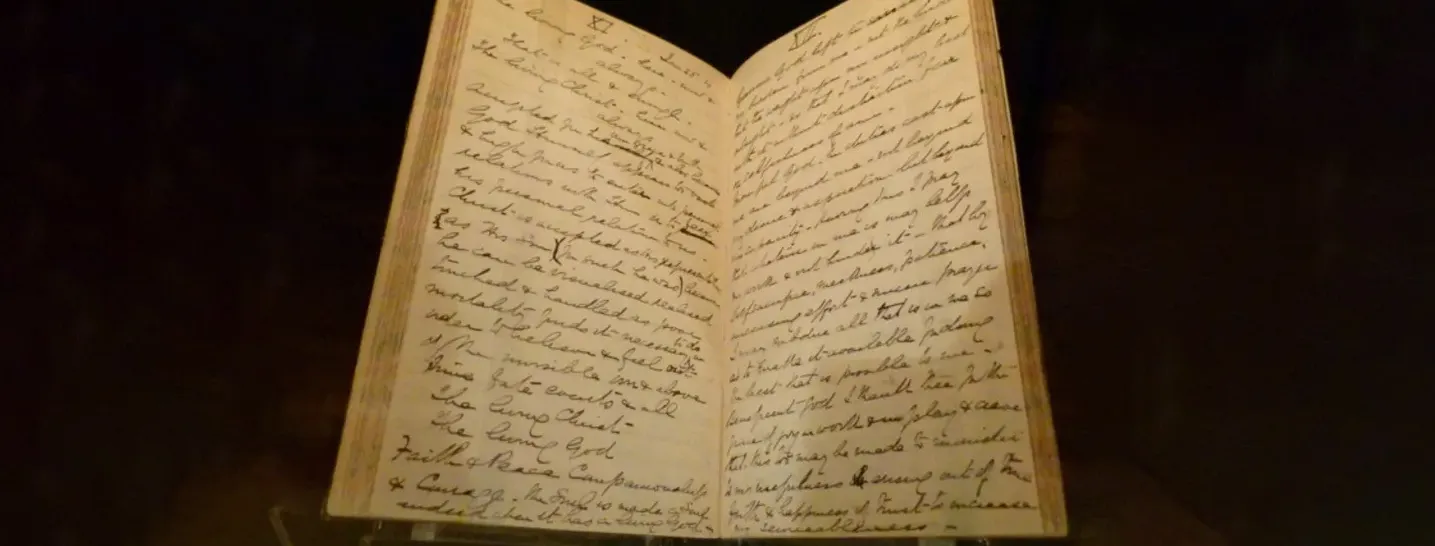

In the Museum's collection are some private writings by Alfred Deakin, prime minister in 1903–04, 1905–08 and 1909–10. Deakin’s Boke of Praer (thankfully only the title spelling is archaic) demonstrates how the act of writing forces a clarity of mind, a purity of thought and, perhaps, a revelation of personality that digital dialogues may never match.

Kindly lent to us by the National Library of Australia, Deakin’s Boke reveals another side of this prime minister’s ‘affable’ public image. Deeply introspective, Deakin had an intense religious faith and sought spiritual transformation through mystical insight into the nature of God. He studied world religions, philosophy and science in order to understand the unity of all life and the wisdom of the universe. He wrote about yoga and karma and, like many people of his era and background, explored mysticism and the Occult. He attended séances and channelled messages from mediums. In 1877 he became president of the Victorian Association of Spiritualists, and was for a short time a member of the Theosophical Society.

Deakin’s ability to psychologically transcend his corporeal self, combined with his intense self-scrutiny, manifested itself in interesting ways. Although he was a qualified barrister, his love of reading and writing—he began composing poetry and plays in his teens—led him to work as a journalist, even while prime minister. In 1901 he became the anonymous ‘Australian Correspondent’ for London’s Morning Post, critiquing Antipodean affairs and the work of someone he called ‘Mr Deakin’!

Deakin filled dozens of notebooks with spiritual and philosophical ideas and wrote his first book of prayers in 1884. Over the next 30 years he scrawled almost 400 prayers, recording his inspirations, reflections and pursuit of a Higher Truth. He believed his political career was pre-destined, and analysed what he perceived as prophetic signs from the Divine. But many of Deakin’s prayers expressed self-doubts, confessed supposed character deficiencies, and beseeched guidance or reassurance. On 24 September 1903, the day he was sworn in for his first term as prime minister, Deakin wrote Prayer XXV:

'On this day of all others it behoves me to crave guidance & support; to put far away from me all that glitters and distracts from the true ends to be achieved by patient conscientious humble effort. Among the much to be done that is meaningless or fruitless O God permit me to discern these things which are necessary for the welfare of the people at large & in which something practical may be accomplished.'

The prayers may also have been a kind of drill written to reinforce Deakin’s discipline and focus. In Prayer XXVII of 4 October 1903 he implored: ‘God grant that I may be Thy minister … in all my public acts and words consciously and unconsciously, willingly and unwillingly, within or beyond my material self’. On 22 November 1903 he wrote in Prayer XXIX: ‘Let me bear my responsibilities rightly – lightly – brightly – without affectation or selfish timidity.’ On February 21, 1904, nine weeks before the end of his first term as prime minister, Deakin’s Prayer XII pleaded: ‘Gracious God lift the sense of my burden from me – not the burden but the weight upon my insight & outsight – so that I may do my best with it without distraction, fear or selfishness of aim.’

Deakin’s use of repetition and rhyme and his studied employment of dualities (‘consciously and unconsciously, willingly and unwillingly’; ‘insight & outsight’) indicates his talent for spoken language as well as his philosophical belief in the balance of all things. Combined with his generous use of hyphens, Deakin’s prayers suggest not just brackets of thought, but also snatches of conversation. Still considered one of the greatest orators in Australian political history, Deakin seems not to have confined his speeches to the public domain. His Boke of Praers reveals the extent of his private physical and mental connection with the Divine. These written conversations may not only document Alfred Deakin’s quest for enlightenment, however. Perhaps they also record the strain of serving the nation.

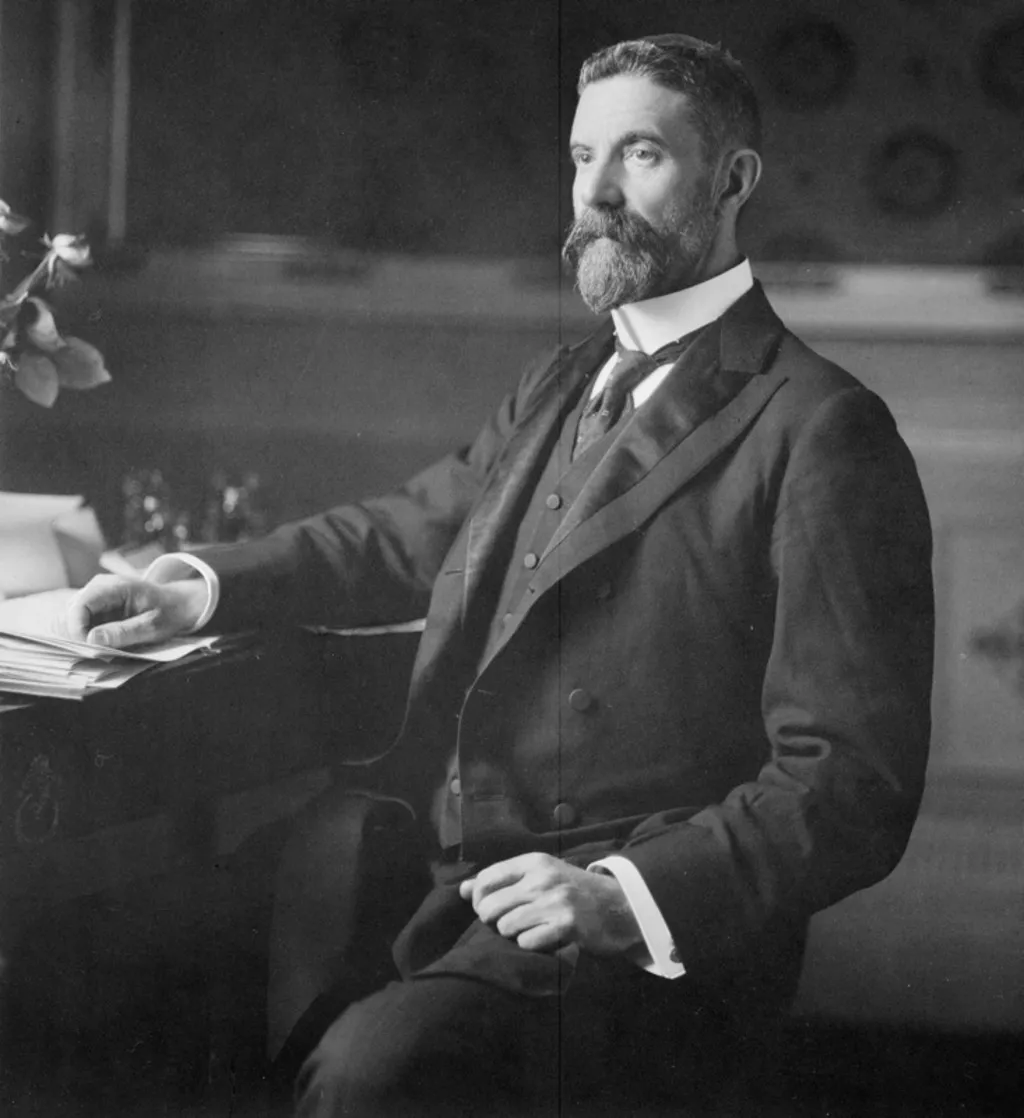

Alfred Deakin c.1901. Image: National Library of Australia.