The Denmans in British Australia: cultured and courteous with nothing to do

- DateWed, 16 Nov 2016

Australia today is not a republic but its culture is in many respects republican.

The governor-general and monarch have their place in the Constitution. But God Save the Queen has been abandoned as the national anthem, and migrants who take out citizenship swear an oath that does not mention her. Royal tours are restrained occasions. The monarchy, in short, is no longer central to the nation's civic life or identity.

Australia of a century ago was a very different place. It's not just that most Australians understood their country to be British, and that Australia was bound to the empire. The country's symbolic, social and civic life were also monarchical and imperial. Australians liked to think of themselves as democratic, egalitarian and informal, yet they were also status-conscious, as well as partial to imperial honours, courtly culture and social hierarchy.

The British historian David Cannadine has explained that settler societies such as Australia often regarded themselves as having a flatter social structure and more democratic culture than Britain – something more like America's – but there was also an influential notion that mature British societies overseas would take on something of the graded and layered character of Britain itself. Government House stood at the head of this understanding of society. Whether one was or was not admitted was a marker of status.

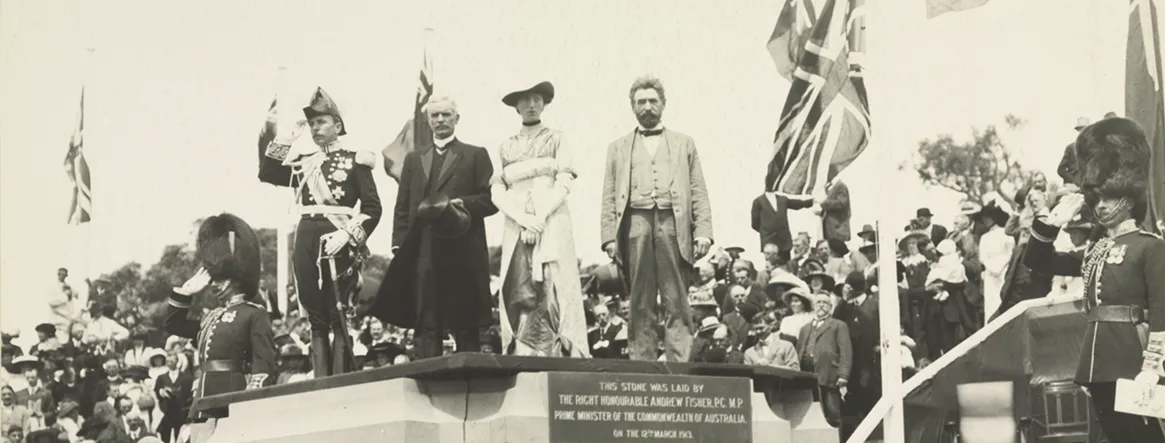

Peers of high standing were in demand for vice-regal office. Cannadine specifically mentions Thomas Denman, Governor-General of Australia from July 1911 to May 1914, as part of 'an unprecedented efflorescence of peers as proconsuls … Marvellously arrayed with plumed hats, ceremonial swords, ribbons and stars, and transported in ostentatious luxury in special trains, they toured their dominions, entertained grandly, made speeches and laid foundation stones'.

Most accounts of Denman's life recognise that he was not one of the giants of his era. He was a contemporary of Winston Churchill at Sandhurst but was rarely in danger of rivalling his drive or distinction. A Boer War veteran who had been wounded, he suffered poor health that trailed him throughout his Australian sojourn. He was not a forceful personality; most accounts agree that he was markedly inferior in this respect and others to his wife, Lady Gertrude – or Trudie.

At the beginning of their time in Australia, he was in his mid-30s, she in her mid-20s, and they had two children. Trudie had a passion for hunting, riding, motoring and women's suffrage but not for her husband. The Denmans' already troubled marriage disintegrated during his term in Australia, as Trudie had a love affair with Denman's military secretary.

Denman's predecessor left him a note that explained that 'there is very little work to do' but there were nonetheless challenges. There was an inherent ambiguity in the role. The governor-general was the representative of the British monarch in Australia, part of the nation's Constitution, and a representative of the British government – essentially a diplomat – answerable to the Colonial Office. Britain had no high commissioner in Australia until the 1930s. But how could the one man be both a confidant to his Australian ministers and the representative of another government?

Denman's own politics, as well as those of his wife, were progressive. He had inherited a title but little money; she was from a famously wealthy family. Both Denmans established friendly relations with the Labor Party people, and Lord Denman had an especially cordial relationship with the Scottish-born prime minister, Andrew Fisher.

In view of his professional background as a soldier, Denman naturally interested himself in defence. Australia, fearful of Britain's ally Japan, instituted a system of compulsory military training as well as creating its own navy, and Denman kept a close eye on matters. There was also much travel for the Governor-General to do. In September 1912 he went to Port Augusta in South Australia to turn the first sod on the Transcontinental Railway. In March 1913, it was to dusty Canberra to lay the foundation stone for the new capital.

Trudie, who announced the name of the new city at the ceremony, was popular for her informal style, her infectious smile and her unpretentious ways. Country folk were astonished when she arrived at one centre in riding breeches and with a cigarette hanging out of her mouth. We get a sense of her manner, as well as of her sense of humour, in a letter to her brother in which she reported that 'I am not allowed to go to any but epoch making functions of a national character. I have to avoid doing anything merely civic or parochial, as that is the department of State Governors' wives. I am also too grand to go into a shop.'

Thomas Denman also had many qualities to commend him to Australians. Handsome, charming, cultured and courteous, he probably conformed to many Australians' image of what an aristocrat should look like and how the best of them should behave. He was a sporty man who loved his horses, and the Denmans were generous with their money – or, rather, with the money of Trudie's family.

In November 1913 Denman wrote to his superior in London asking him to accept his resignation. Ostensibly, the reason was his health, but marital problems are also likely to have played a part, and Denman had become too much of an advocate for the perspective and interests of the Australian government.

On 14 May 1914 the Denmans left Melbourne for home. The radical Labor Call thought him a 'good' and 'amiable' fellow, while concluding that 'he has done nothing, because he had nothing to do, and he did it well'. Mainstream press coverage was more generous: 'He had a marvellous power of restraint, a keen scent for the pitfalls of controversy, and a genial tact and adaptability'.

The wattle had emerged by this time as a symbol of Australia, so there is perhaps something slightly comical about Denman being so prone to hay-fever that it had to be banned from public functions he attended. Nevertheless, the Denmans were also the right people in the right place at the right time.

The years 1911-1914 were, for Australians, a time of peace and of optimistic nation-building, tempered by growing fears of international conflict. The Denmans behaved in ways that neither gravely offended their occasionally touchy hosts, nor damaged the office of governor-general. They were in tune with their times and, perhaps more surprisingly, with the people and place as well.

This article was prepared in conjunction with a talk delivered by Frank Bongiorno at the Canberra Museum and Gallery (CMAG) exhibition Peace, Love and World War: The Denmans, Empire and Australia 1910-1917.

The first outdoor entertainment hosted by the Denmans at Government House, Sydney, on a ‘peerless’ Spring day, October 1911. Perhaps conscious of Lady Denman’s penchant for a good hat, Sydney’s socialites respond to the challenge. From the Lady Barttelot album, Collection of Lady Margot Burrell.

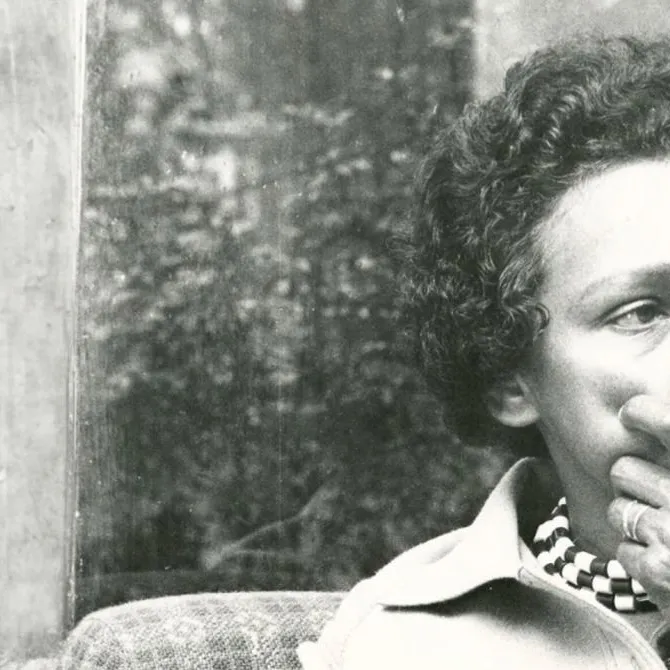

Sir William Nicholson (1872-1949), Lady Gertrude Denman. Oil on canvas, c.1909. Collection of Lady Margot Burrell.

Max Meldrum (1875-1955), The Rt Hon Thomas Denman, Baron of Dovedale GCMG KCVO PC JP, 1914. Historic Memorials Committee, Parliament House Art Collection, Canberra ACT.