Zines from the Refugee Art Project

- DateFri, 09 Apr 2021

Sydney-based artist, musician and academic Safdar Ahmed has been facilitating the making of zines that share the art and stories of people incarcerated in the Villawood detention centre.

We spoke to Safdar about how these highly personalised publications offer a vehicle for self-expression, as well as the creative and technical processes involved in bringing zines to life.

Can you tell us about the zines you help to create as part of the Refugee Art Project?

From 2011 until about 2017 some friends and I would go every Saturday afternoon to Villawood with sketchbooks, pencils, drawing pens, and delicious chicken from the al-Jannah chicken shop in Granville. The gatherings were unstructured and casual, depending on people’s mood and enthusiasm. Eating, chatting and occasionally drawing became routine and people who, for the most part, had never made art before began to develop some really powerful and amazing images.

Most of those we met were refugees from Iran, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar and many had been held for around two years, after committing no crime, with no idea of when they would be released. This created intense uncertainty, stress and illness, and so our gatherings weren’t really ‘workshops’ as such, but social events where people could relax amongst friends and try to draw something for fun or to develop a new skill.

From there some of our participants discovered an aptitude and enjoyment for art, and a few told me they did it as a point of immersion and relief from the daily stressors of being locked up. I think a lot of the work in our zines is important both for its aesthetic power and also as a type of historical record, showing in many ways the damage that Australia’s detention system can do to people, but also the agency, creativity and resilience of those who survive it.

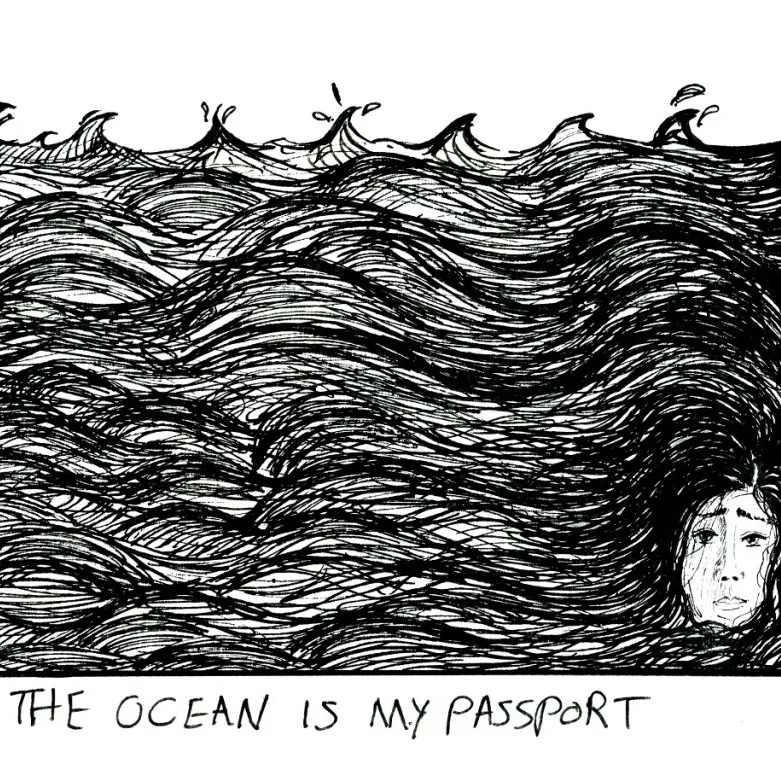

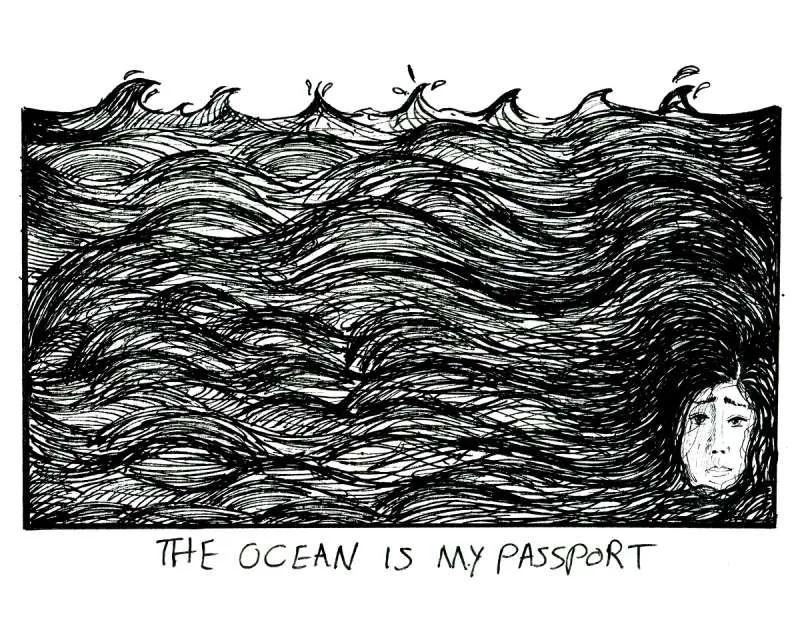

Mona Moradveisi, 'The ocean is my passport'.

How do zines enable refugees and asylum seekers to share their stories?

I think zines are a great format insofar as they are cheap to produce and there is no need for the type of editorial oversight you might get when working for a journal or magazine. Most of our participants chose anonymity or a pseudonym to protect their identities as a matter of privacy, and because their refugee claims were still in process and we didn’t want to do anything that would endanger that.

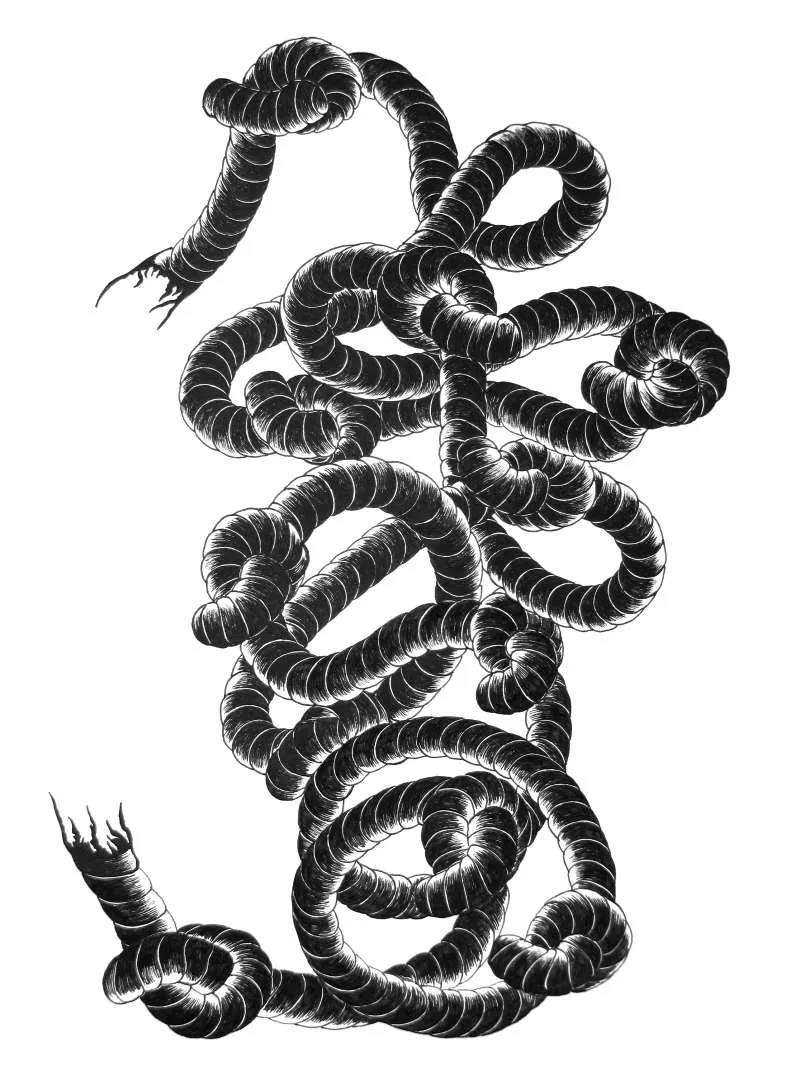

Also, people were free to present images or narratives on their own terms. For some, this meant grasping the opportunity to address their political situation. Some would depict the difficulties they faced in their home country, or the punishment they were experiencing in detention. For others it was the chance to practice culture in myriad ways, to draw religious symbols or deities, or to develop escapist or fantastical themes. I think all of the work (like any art) is underwritten by the context of its creation and the circumstances under which it emerged, so it clearly wasn’t made under the ‘normal’ circumstance in which most people engage in creative practice.

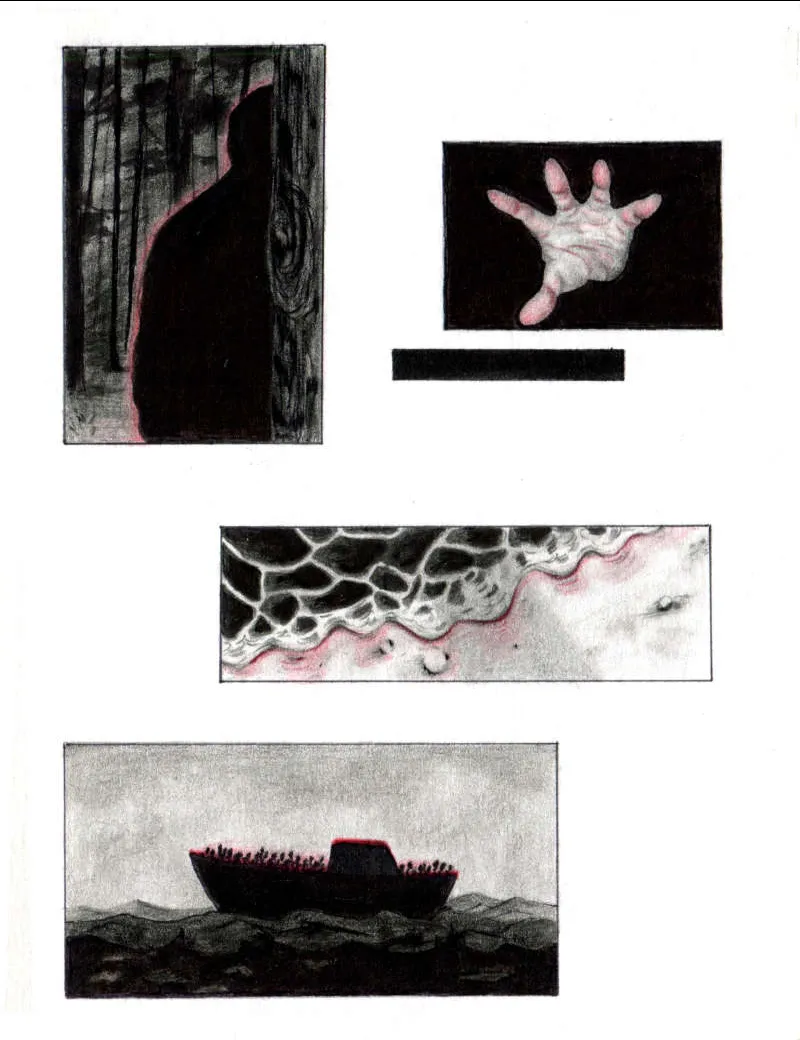

Tabz A, 'The Journey'. Tabz A came to Australia as a refugee with her family in 2012. She and her older sisters were some of the first students to graduate from high school while incarcerated.

Can you describe the process of creating the zines?

Because the detention centre was so restrictive in terms of what materials we could take in for people, simple sketchbooks, pens and pencils were the main tools of expression. There were one or two people who painted on canvases in their rooms but that was tricky. Because it is flammable, turpentine was forbidden so someone painting in oils would have to wash their brush with soap and warm water. A medium like linseed oil had to be delivered in a small plastic container, because glass was forbidden. One detainee had knitting needles taken away because the officers said he would probably end up harming himself! So under those conditions, sketchbooks were the easiest thing.

The people whose work is featured in our zines were consulted closely so it was definitely a collaboration regarding what would be printed and how the work should be presented. Taking objects out of the detention centre was always tricky because they wanted you to put the stuff through property, and one time they lost someone’s canvases in the process, but drawings were easily slipped into my sketchbook and taken out under the arm. We would scan the images and put the books together in InDesign. A PDF was sent to the printers, to return as books a few weeks later.

What has been the reaction from those contributing to the zines as well as the people reading them?

I hope the zines give the people who made them a feeling of agency, accomplishment and pride. It’s always exciting to see work you’ve made compiled in print and many of the individuals who have zines on their art have asked for extra copies to give to people as gifts, which is nice to see. Regarding the public I hope people are shocked by Australia’s treatment of refugees but also struck by the power, depth, variety, quirkiness and richness of the work on display.

Refugees should not be viewed only through the lens of their trauma or persecution, which is a reductive and ultimately demeaning way to be framed. Against this I think our zines reflect the richness and complexity of people’s experiences, which hopefully provides a fuller, more realistic picture of how people assert their agency and personality than the shallow stereotype of the poor, suffering refugee who needs our ‘help’.