1928: State debts

Lend us a tenner

Date

17 November 1928

Question

Do you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled 'Constitution Alteration (State Debts) 1928'?

Result

More than two-thirds of Australians voted YES, and the measure passed. The Constitution was changed.

NSW

Yes: 754,446 (64.5%), No: 415,846 (35.5%)

VIC

Yes: 791,425 (87.8%), No: 110,143 (12.2%)

QLD

Yes: 367,257 (88.6%), No: 47,250 (11.4%)

WA

Yes: 96,913 (57.5%), No: 71,552 (42.5%)

SA

Yes: 164,628 (62.7%), No: 98,017 (37.3%)

TAS

Yes: 62,722 (66.9%), No: 31,044 (33.1%)

Total

Yes: 2,237,391 (74.3%), No: 773,852 (24%)

If you live in Devonport, should your needs be subsidised by the taxes paid by people in Sydney? And who is responsible for making that decision? The 1928 referendum asked Australians to change the way finances were managed by the Commonwealth and the six states. Unsurprisingly, the whole thing was extremely complicated.

When the six British colonies came together to form the Commonwealth of Australia each gave up a lot of their economic power, like the right to levy certain kinds of taxes. The colonies agreed to Federation because they were promised funding and loans from the new federal government. The Constitution guaranteed the Commonwealth would take over any debts incurred by the states for ten years. By 1910 it was obvious that arrangement would need to be extended, so the constitution was changed to make it permanent. A system of grants was established to finance the states, but they were capped at a certain level. By 1927, they had become inadequate due to inflation.

A whole new approach was needed. The states needed a good supply of finance, and the Commonwealth needed to have limits on how much it would give to the states. The Bruce Government made a new agreement in 1927 with the six state premiers to establish a Loan Council, which would approve all loans to states and co-ordinate borrowing between governments. Only one problem: the rules around finance, as written in the Constitution, weren't clear on whether the new body was allowed. Some of those provisions were very specific and outdated, and others were ambiguous. To make sure his new system was watertight, Prime Minister Stanley Bruce called a referendum to make his new agreement explicitly and clearly constitutional.

The proposed change was difficult for many voters to understand, and they weren't helped by the lack of any official material laying out the arguments. Because the referendum was held at the same time as a federal election, Parliament passed a law which said no such material could be sent out to voters.

The referendum passed with a large majority, possibly due to it having bipartisan support and there being little argument against it in the press. The money kept flowing and state governments were happy – most citizens, in fact, probably didn't notice the difference. The Loans Council, as it is now known, continues to this day, helping state governments keep the lights on and allowing big projects to be funded for the benefit of citizens.

How to Vote card for the seat of Kooyong, asking voters to vote 1 for their local member, Attorney General John Latham, and for a YES to the referendum question, 1928. Voters were asked to preferentially rank their response to the referendum, but contemporary referendums ask voters to write ‘Yes’ or ‘No’.

Museum of Australian Democracy collection 12489

The YES case according to Stanley Bruce

'This referendum is designed to give power to the Federal Government to make financial agreements with the States. At the present time the Commonwealth does not possess that power, and irrespective of the necessity or desirability of placing our national and State finances on a sound basis, unless the referendum is passed we shall be unable to act.

There is no difference of political opinion on this measure as far as all the State and Federal parties are concerned. In fact the States, including those now governed by Labor, have by ratifying the agreement expressed their full approval of the principle to be decided. I wish to emphasise that by passing the referendum you do not vote for a particular form of financial agreement, you merely make it possible for the Commonwealth and States to give effect to any agreement jointly decided upon.

The leader of the Federal Labor Party (Mr Scullin) is also in favor [sic] of giving the Commonwealth the proposed power and I trust that you will, by casting your vote in the affirmative on election day, help to bring about a reform upon which all intelligent members of the community are agreed and which is indeed essential for our future progress as a nation.'

Source: Statement by Stanley Bruce as reported in The Age, 13 November 1928

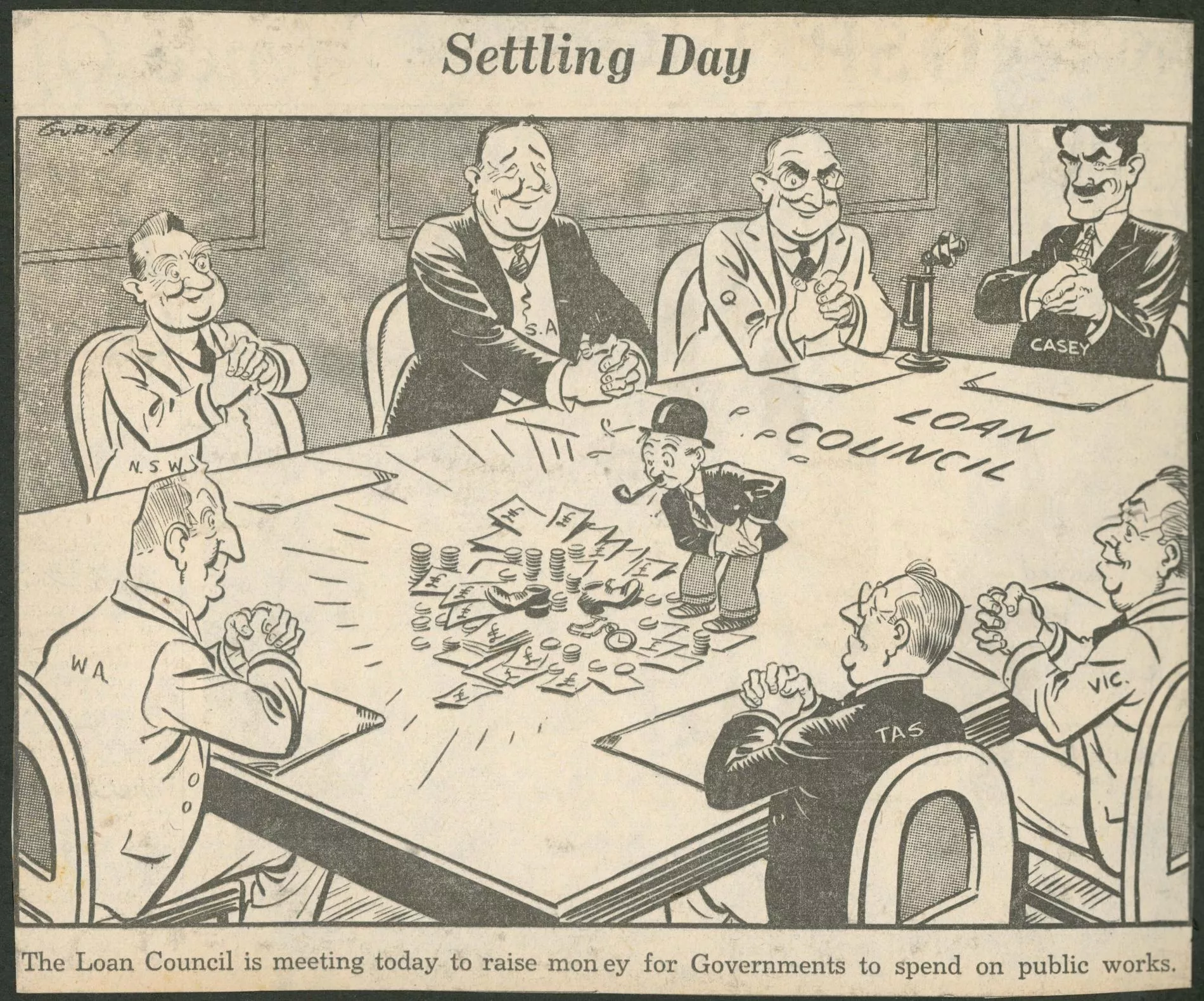

Cartoon depicting the Loan Council, about 1936 (artist unknown). The 1928 referendum enabled a new kind of Loan Council to manage the finances of the country and the States, but as this cartoon from about 1936 shows the process was far from smooth. Depicted are then-Treasurer Richard Casey and the 6 state premiers in office at the time.

National Archives of Australia M3130, 81

The NO case according to South Australian Labor leader Lionel Hill

'The Prime Minister in his policy speech was vague, and practically the whole of the supporters of the Government were treating the matter with indifference. The wording of the ballot conveyed nothing to the electors. It was to be regretted that the Commonwealth Government had not taken adequate steps to impress upon the electors the great importance of the vital alteration proposed...and that a referendum so far-reaching should be held on the same day as a general election where side issues, too numerous to mention, were being raised. The general elector had limited opportunities of gauging the merits or demerits of such intricate agreements from the debates in Parliaments. The elector was now being asked to decide the question blindly.

South Australia would lose in 38 years approximately £31,000,000. There could be no sound objection to a voluntary Loan Council...but there was a distinct objection to the establishment of such a council which abrogated the sovereign rights of the States.

To seek amendments in a piecemeal fashion...was courting complications and leading to disaster. It was unification by financial strangulation. The States would not be relieved of their costly burdens...

In his opinion the safe course for the electors of the State was to vote "No". If the referendum was defeated the Commonwealth Government must then completely review the financial position.'

Source: Report of a speech by Lionel Hill, Leader of the (Labor) Opposition in South Australia, in the Adelaide Register, 7 November 1928

Did you know...?

This referendum was passed by all 6 states; in 1910 a referendum on a different aspect of state debts also passed.