1937: Aviation

Come fly with me

Date

6 March 1937

Question

Do you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled 'Constitution Alteration (Aviation) 1936'?

Result

A majority of Australians voted yes, but only 2 states voted in favour. The Constitution did not change.

NSW

Yes: 664,589 (47.25%), No: 741,821 (52.75%)

VIC

Yes: 675,481 (65.10%), No: 362,112 (34.90%)

QLD

Yes: 310,352 (61.87%), No: 191,251 (38.13%)

WA

Yes: 100,326 (47.58%), No: 110,529 (52.42%)

SA

Yes: 128,582 (40.13%), No: 191,831 (59.87%)

TAS

Yes: 45,616 (38.94%), No: 71,518 (61.06%)

Total

Yes: 1,924,946 (53.56%), No: 1,669,062 (46.44%)

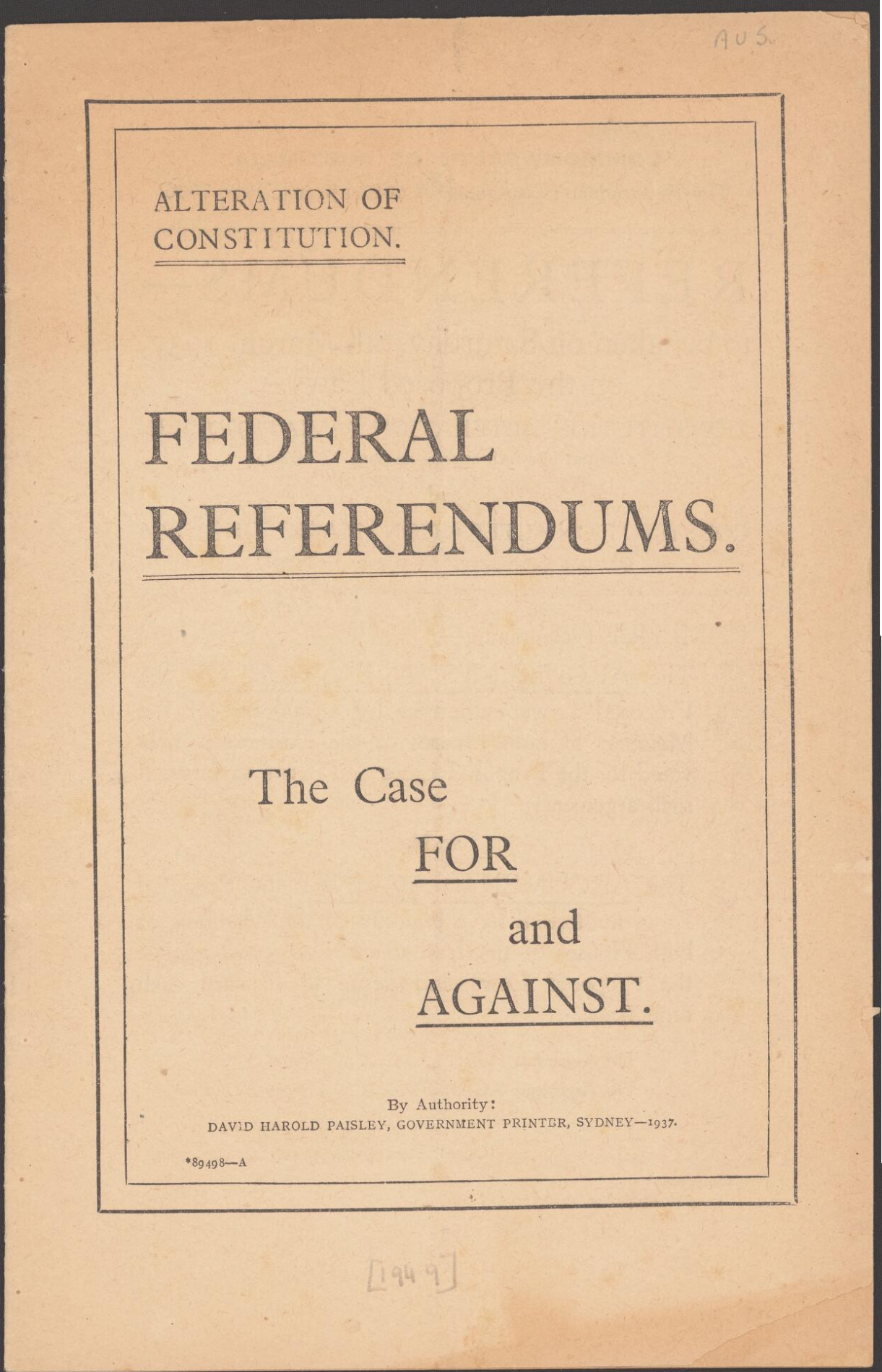

The extensive booklet outlining the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ cases, sent out to homes for both the question on aviation and another question about marketing (prices and sales), 1937. Voters rejected both proposals.

National Library of Australia

When the Constitution came into force in 1901, powered aviation was a fantasy and for obvious reasons government responsibility for air travel didn't rate a mention. But the Wright Brothers' successful flight in 1903 ushered in a new era, and by the 1920s aviation had become a viable means of transport. So, if the Commonwealth wished to regulate air travel, they ran into a constitutional hurdle. Who decided what a safe aeroplane was, or where and how it could be flown? A 1937 referendum sought to give the Commonwealth the legislative power with respect to air travel, and even though it failed, the very attempt gave momentum to change.

If the Commonwealth had the power to control aviation, the dominance of rail travel was under threat. States relied on rail for trade and commerce, but all state premiers saw the need for change in the national interest. A Royal Commission held in 1929 recommended an aviation power be added to the Constitution. Almost a decade later, the issue was becoming more critical as aviation became more common. To finally settle it, Prime Minister Joe Lyons’ government called a referendum on the issue.

Attorney-General Robert Menzies ran the YES case while the NO arguments were prepared by members of the New South Wales parliament. Because the proposal was so complex, the booklet distributed to households outlining the arguments was a whopping 22 pages long. The newspapers also had strong opinions – most, including the Sydney Morning Herald and the Argus, supported a change and reported that the YES vote was more likely to win.

The YES vote won nationally, and in Victoria and Queensland, but the other states returned a NO majority, in some cases quite narrowly. Since it failed the 'double majority' requirement, the proposal was defeated. The government, however, was undeterred. The referendum campaign highlighted the inadequacy of existing laws, and another solution was needed.

Eventually, the Commonwealth came to regulate aviation under the external affairs power within the Australian Constitution, due to international treaties on air safety. It turned out that the actual amendment, while it would have made things easier, wasn't necessary but the referendum brought momentum for reform to reflect the changing world.

Extract from the official YES case

'Object – To enable what is obviously a national problem to be dealt with by the National Parliament. Under existing powers the Commonwealth may control interstate, but not intrastate, aerial transport. It is ludicrous that the transport instrument, so flexible and so incapable of being kept within narrow geographical limits, should still be in many ways subject to different sets of Commonwealth and state laws. The real question is whether the people desire divided or unified control. Federal regulation of aviation means the greatest simplicity and certainty, and the greatest safety in flying.'

Source: Summary of arguments in the Launceston Examiner, 12 January 1937

Aviator Charles Ulm, Prime Minister Joe Lyons and an unknown man with Ulm’s plane, the Faith in Australia, 1934. Ulm disappeared without trace only a few months later, showing the new aviation technology had both dangers and benefits.

National Library of Australia PIC/8392/287 LOC Album 1033/4

Extract from the official NO case

'The Lyons Government plans to hand over air transport to an Imperial Airways Trust. A "Yes" vote will mean dearer freights and fares for people in every state. The revenue loss will not go to the Commonwealth Treasury, but to an Imperial Air Trust, which has become a sinister influence in the political life of Australia. A "Yes" vote will wreck the state railway systems, in which the electors have invested £311,486,688. A monopoly to an Imperial Air Trust will bankrupt country towns and mean dearer freights and dearer food.'

Source: Summary of arguments in the Launceston Examiner, 12 January 1937

Did you know...?

This was the first referendum in which the change was supported by a majority of Australians, but which failed because it lacked support in a majority of states.