Free votes: a quick explainer

- DateWed, 09 Aug 2017

It's tough to be a politician. You are called upon to represent the community that elected you, but you're also called upon to follow a party line, and support whoever your party's leader is.

Sometimes, those two goals might be in conflict. Then what do you do? Stand on your principles, or be a team player? You might be lucky enough to be given a free vote. But what does that mean?

What is a free vote?

A free vote, also called a conscience vote, means a Member of Parliament or Senator can vote whichever way they like, free of any consequences from their party or leader. Usually, conscience votes are on issues of life and death, or controversial social legislation. In order to have a conscience vote, a party's leadership must grant it to its MPs. Often, but not always, both major parties agree to a free vote.

How often are free votes held?

Free votes happen, on average, once per parliamentary term. During the 11-year Howard government, there were only five votes that weren't on strict party lines. There was only one during the Rudd–Gillard era.

If they're so rare, what happens during other votes?

The rest of the time, politicians in Australian parliaments vote along strict partisan lines. Voting against your party is called 'crossing the floor' and can have very serious consequences. Labor MPs and Senators are usually expelled from the party for doing so and, while Coalition MPs have more freedom in that regard, if they do it too often they still risk the ire of their party or leader. This is in contrast with, for example, the United States, where Democrats and Republicans in the Congress frequently vote according to their own views. International experts have described Australia's party system as unusually tight – in most other countries, the act of crossing the floor is more common.

All parties employ officials called 'whips', whose job is to ensure MPs and Senators vote the right way. Defying the whip can be a career-limiting move!

What issues have there been free votes about?

Issues and bills decided on a conscience vote have included:

- Decriminalising of homosexuality in the Australian Capital Territory (1973)

- Abolition of the death penalty (1973)

- Introduction of no-fault divorce (1974)

- The Sex Discrimination Act (1984)

- Euthanasia laws applying to the Northern Territory (1996)

- The republic referendum (1999)

- Prohibition of human cloning and stem cell research (2002 and 2006)

- Introduction of abortion drug RU486 (2005)

- Same-sex marriage (2012)

Why are they so rare?

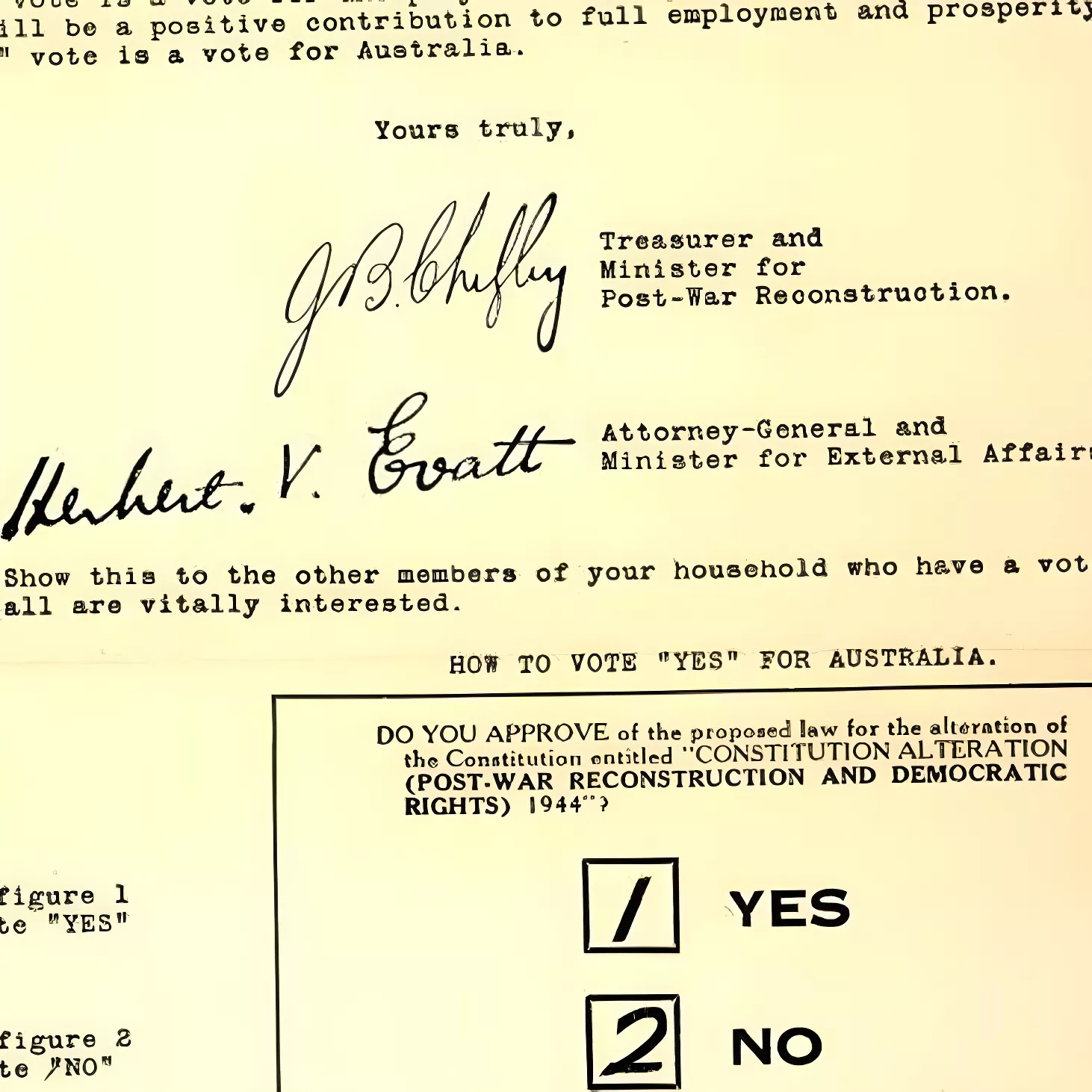

In the early days of the Commonwealth Parliament, the party system was much more relaxed. People usually nominated and sat as a member of a party, but parties had different names and views in different states, and there was an expectation MPs would vote according to their conscience. The Labor Caucus, however, instituted a rule that all Labor MPs would be bound to vote the way the party room decided. This gave them enormous bargaining power, since it meant any agreement with Labor MPs could guarantee a large number of votes. It took less than a decade for the non-Labor parties to adopt a similar system, which has continued to this day.

Should there be more conscience votes?

Some people, in and out of parliament, think MPs should vote according to their personal views more often. Marriage equality advocates, for example, believe a bill would already have passed if MPs could vote with their conscience, since the majority appear to be in favour. The argument against it, however, is that MPs are elected to represent a party, and to vote whichever way they please means the parties become meaningless.

Edmund Burke, the 18th-century English philosopher seen as a founder of modern conservatism, once said an MP was duty-bound to vote his conscience.

- Edmund Burke, Speech to the Electors of Bristol, 3 Nov 1774