Hanging on the Computerphone

- DateThu, 17 May 2018

Vintage office tech is an abiding interest for visitors to the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House.

If you lurk outside the offices recreated to present different eras of the building, you overhear visitors commenting on the IBM ‘golfball’ typewriters and the rotary dial telephones. But, on the Telecom Computerphone they are silent and that is because there isn’t a single one on a single desk. We have just one lone but magnificent specimen in a showcase, resembling the binary dinosaur that it became.

The story of the Telecom Computerphone is intriguing. The combo of computer and telephone sounds suspiciously like a smartphone but try casually tossing a Computerphone into your handbag or pocket and you will be immediately reaching for a trolley. Join us for a vintage tech wallow…

The Telecom Computerphone had its glorious moment in the sun and on desks in the mid-1980s. An early move into the data terminal market, this computer-telephone hybrid was developed by International Computers and Sinclair Research. Boasting 'all in one' credentials, it launched in Britain as the One Per Desk in 1984 and was rebadged the Computerphone for the Australian and New Zealand market.

Let’s look at what this baby could do for the politicians and staff of Parliament House.

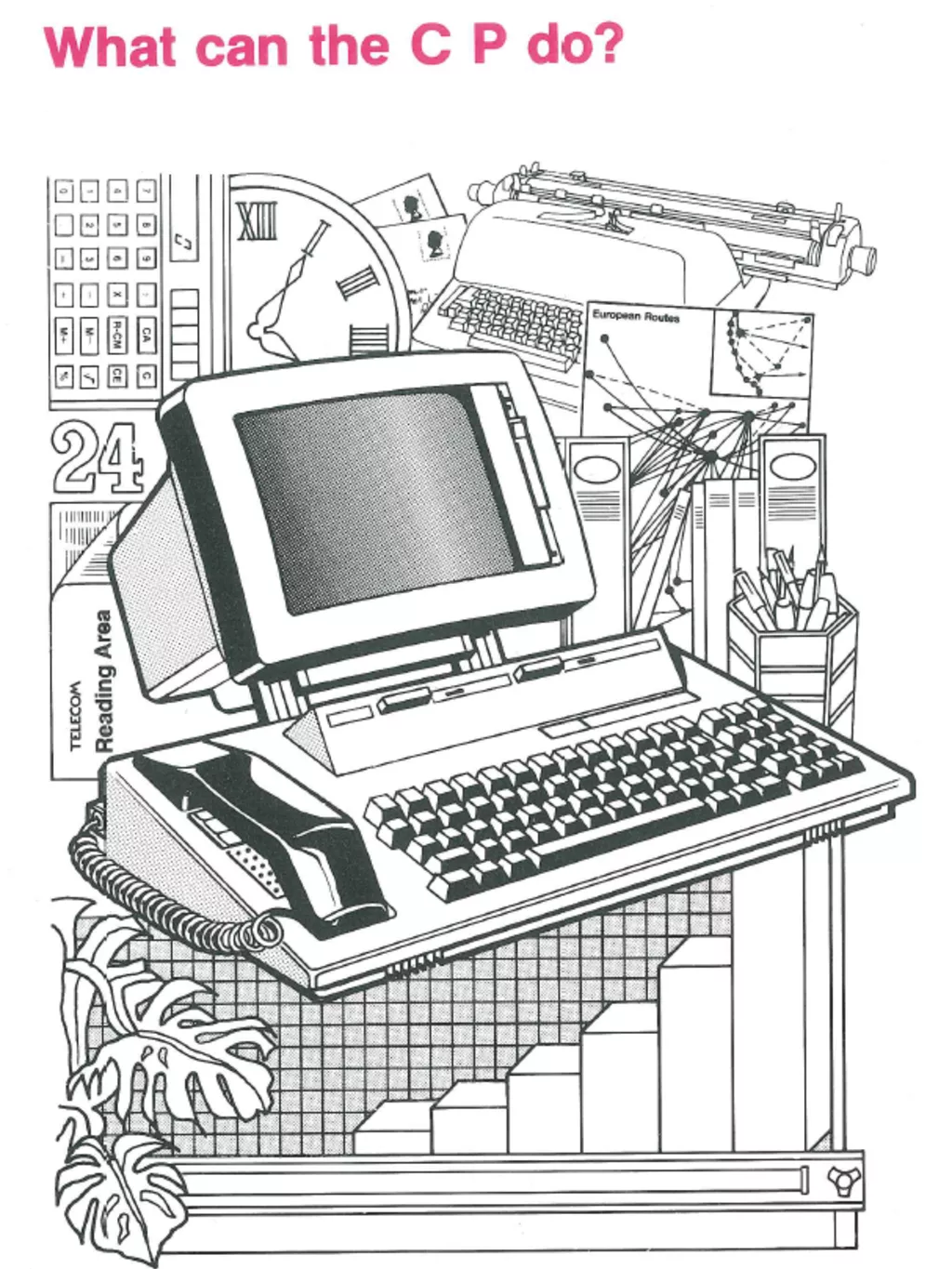

Begone clunky manual typewriter and stamped snail mail, die boxy calculator and disappear clock with hands, vanish technical drawing slope and pencils and pens. So yesterday. Here comes the Telecom Computerphone to clear your desk of redundant tech.

Yep, as well as a telephone with loudspeaker and a speech synthesiser for automatically answering calls, you got a four-colour monitor, BASIC programming, a calculator and a suite of custom software including Quill word processing, Abacus spreadsheet and Easel business graphics. The user could also access Telecom’s Viatel service, Australia’s ‘internet before the internet’, using the built-in 1200/75 baud modem. It sounded great.

But the Computerphone cost. A lot. Like a staggering $4,400 if you opted for the attractive colour monitor. In the 1980s, Parliament House accommodated 224 politicians with 370 support staff and then there were all the parliamentary departmental staff. That is a lot of Computerphones on desks.

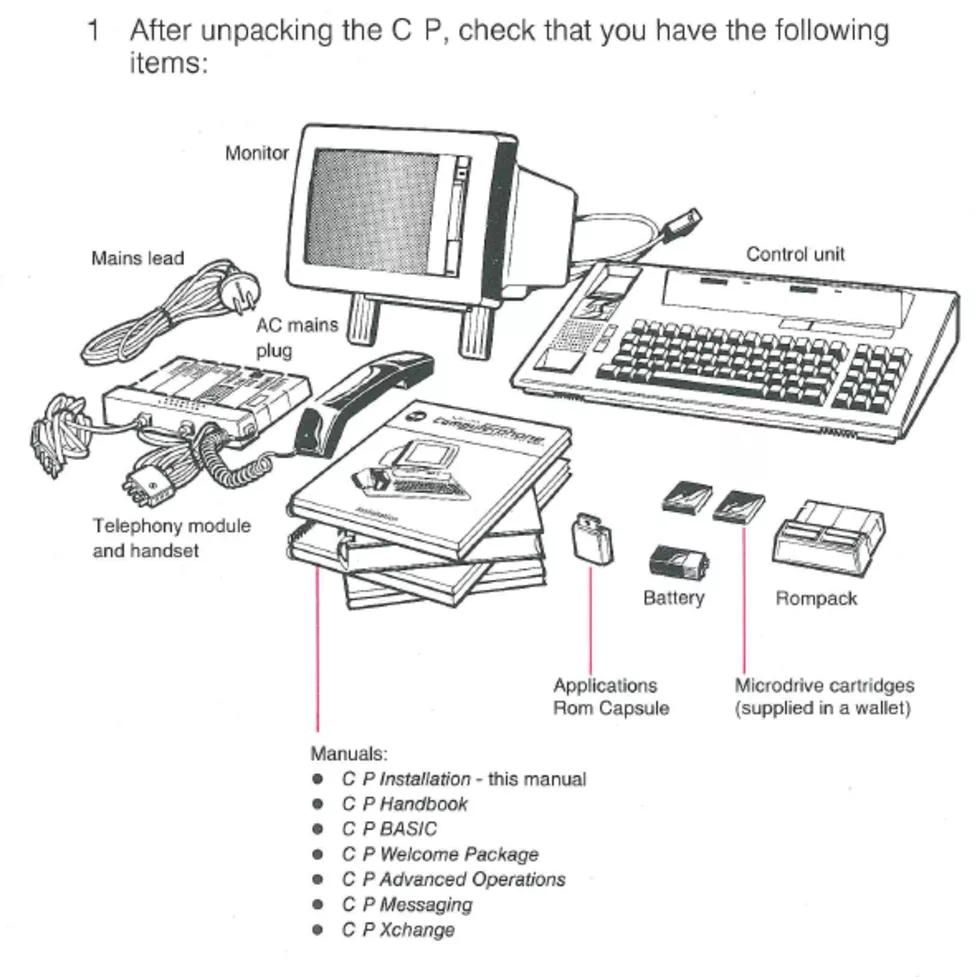

But, did it promise value for money? Let’s unbox.

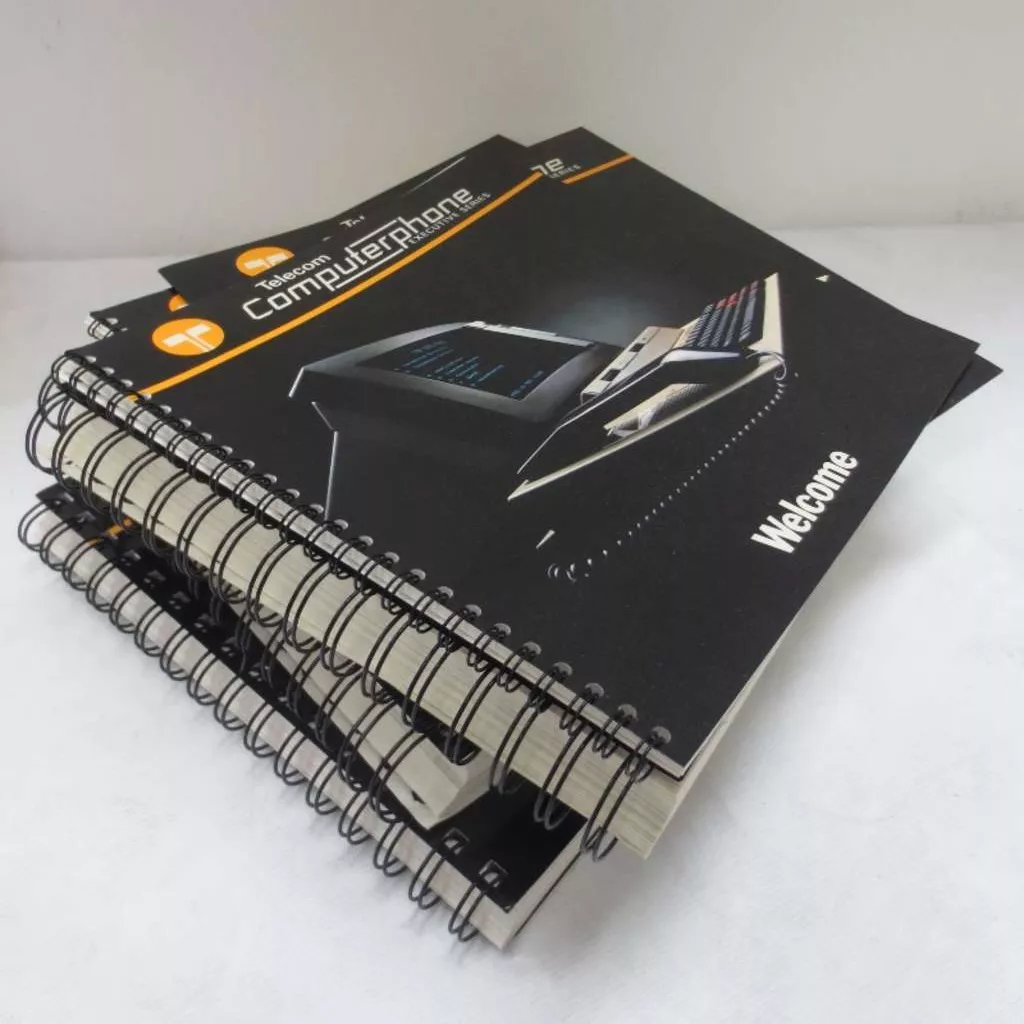

Ah, tech heaven. Lots of components, snaky cables and leads, fiddly micro-things. In short, hours of set up fun. The crowning glory for this particular product? A towering stack of no less than seven manuals – Installation, Handbook, BASIC, Welcome Package, Advanced Operations (!), Messaging, Xchange.

The Computerphone even had a brief moment in the spotlight on Beyond 2000, a popular science and technology program that aired in the 1980s and 90s. Billed the ultimate in flexible work tools, the Computerphone scored a fleeting segment. It all looked so promising.

So, why haven’t you heard about this giant in the tech world? Why wasn’t there one on every desk in Old Parliament House?

Unfortunately, the Computerphone was a commercial disaster that was left in the wake of the IBM PC juggernaut. Instead of using DOS like most computers of the day, Telecom decided to develop a brand new operating system. This meant the Computerphone wasn’t compatible with IBM or Apple or Commodore or any other computer built before or since. The concept was innovative, even ahead of its time, but the journey to market was a glacial four years and the execution was poor.

The case was flimsy and the choice of microdrives instead of the popular 5¼-inch floppies was puzzling. The microdrives were easily lost, slow to load and you couldn’t transfer data to any other system. Towards the end of its five-year life span, the monitors failed to such an extent that Telecom started issuing two replacements whenever one broke down.

So, why has the Museum of Australian Democracy collection been blessed with this object? In the mid-1980s, Barry Jones, then Minister for Science, was presented with a snazzy Computerphone. He thought it was terrific. Neil Baker, a telephone technician at Old Parliament House and keen collector of all things telephony, eventually acquired it for his personal collection and donated it to the museum collection in 2006 along with other fab phones.

For those who believe there is no such thing as too much vintage tech, join Terry ‘Tezza’ Stewart as he fires up his working model.