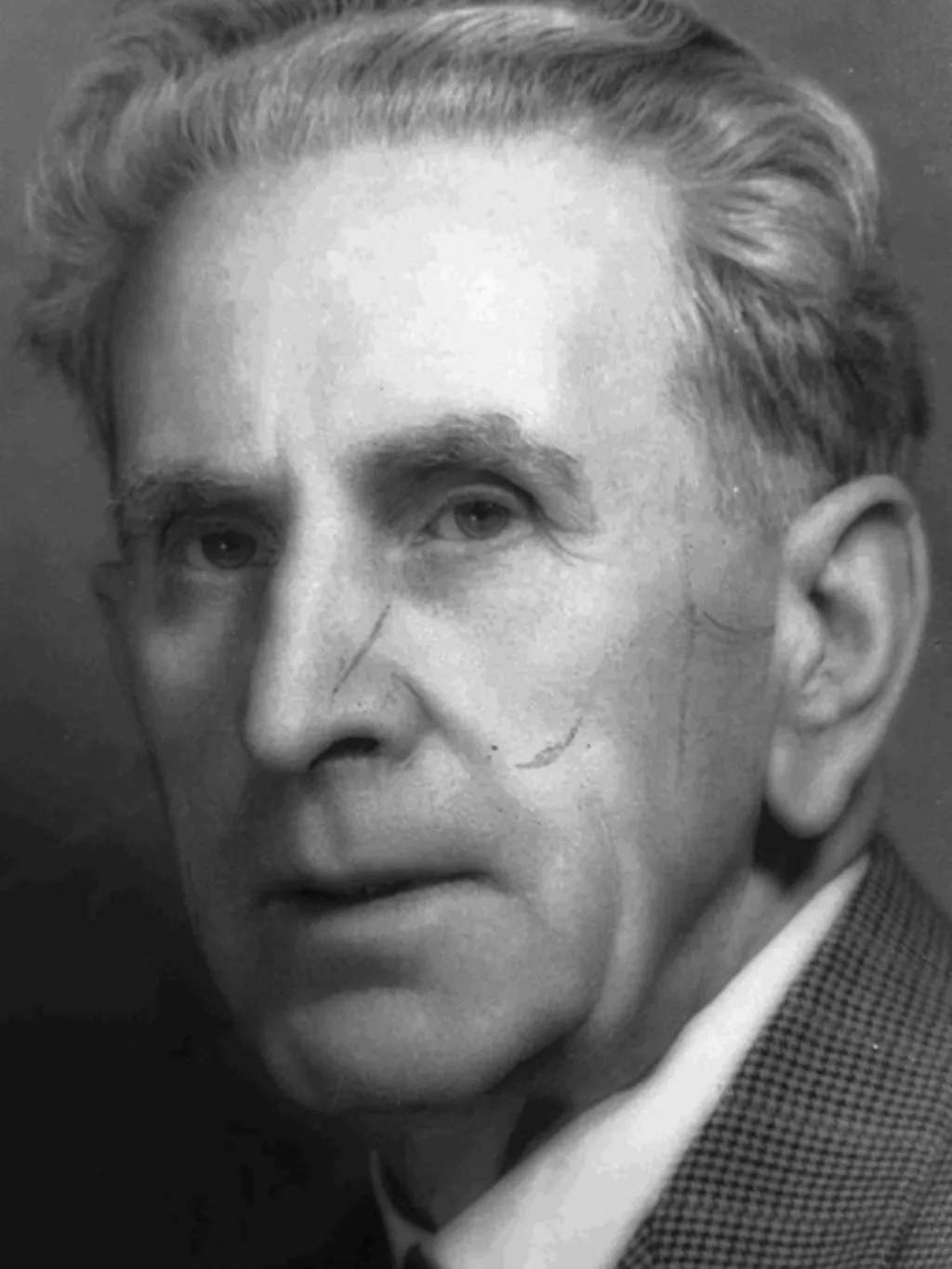

Donald Grant – from gaoled Wobbly to elected Senator

- DateFri, 25 Nov 2016

Of the twelve members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) sentenced in 1916 for conspiracy, none is more fascinating than Donald MacLellan Grant.

Grant’s words in the Sydney Domain following the imprisonment of IWW leader, Tom Barker, that it would cost the capitalists £10,000 for each day served by Barker, had been seen by the state as evidence that he, and other Wobblies (as the IWW were known), were behind a series of arson attacks on business premises in Sydney.

The Twelve were gaoled for conspiracy to commit arson and to incite sedition and pervert justice. Grant was sentenced to 15 years’ gaol.

According to the Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, Grant was ‘spare of build with flaming red hair and a striking appearance … a gifted mob orator able to captivate, inspire and arouse his audiences’.

When the Twelve were released early, following a New South Wales Royal Commission in 1920, Grant’s revolutionary enthusiasm was undiminished. A celebration of their release filled the Sydney Town Hall. Women distributed red camellias and the proceedings concluded with a rousing version of ‘The Red Flag’. Federal MP Frank Anstey and NSW MLA Jack Brookfield shared the platform and Grant, with typical passion and in his Scottish brogue, made it clear he was unbowed. He said: ‘If it is a crime to raise one’s voice against the taking of men from this country to be slaughtered in Europe, we are proud of being called seditious conspirators.’

Yet five years later, he was standing for the Senate for the Australian Labor Party (ALP), the party the Wobblies had condemned as ‘fakers’ and the parliament they had seen as a dead-end in the struggle to overthrow capitalism.

According to Ian Turner in his meticulous account, Sydney’s Burning (1969), most of the Twelve ‘had had their fill of notoriety and were happy to abandon public life’. Not so Grant and two others, Tom Glynn and J. B. King. The latter two joined the new Communist Party of Australia while Grant backed the Industrial Socialist Party (ISP), unsuccessfully standing as a candidate in the federal election of 1922.

The ISP had been established by radical socialist ALP members but after Labor adopted the Socialist Objective in 1921, ISP members gradually moved back to the party.

Grant joined the ALP in 1923 and remained active on the militant left. In 1927, he was again gaoled, for a week, over an unauthorised street demonstration protesting the execution of anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti in Massachusetts. In 1931, he was arrested once more, this time for using insulting words to a policeman in the Sydney Domain.

Grant’s acceptance of the ‘parliamentary road’ may also have been influenced by the fact that it was a Labor State government which called the Royal Commission leading to the release of the Twelve.

Grant’s candidature for the Senate in 1925 was highly controversial within the ALP and he was unsuccessful in the Senate election but, in 1931, he was elected to Sydney Municipal Council and also appointed to the NSW Legislative Council by Premier Jack Lang. He served as an Alderman for 13 years but declined to seek re-election for the Legislative Council in 1940, condemning it as ‘even worse than the House of Lords’ in its representation of privileged interests.

He worked as a dental mechanic in Sydney – the job he had been trained for in his youth in Scotland prior to migrating in 1910 – and again sought ALP Senate endorsement in 1943. This time he was successful.

Senator Don Grant served in the Senate, representing NSW, from July 1944 to June 1959. During that time he was an adviser to the Minister for External Affairs, Dr H V Evatt, and attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1946. While on overseas parliamentary duties he was able to make a visit to Inverness, Scotland, where he was born in 1888.

Grant had moved well away from the politics that led to the gaoling of the Sydney Twelve and was basically a Keynesian anti-communist ‘socialist’. His main interest in the Senate was foreign affairs. He was hostile to the Soviet Union, supported recognition of the Peoples Republic of China, opposed apartheid in South Africa and expressed the view that Australia’s future was bound up with the Asian region.

It’s a pity that an oral history interview was never recorded with him. He died in 1970.