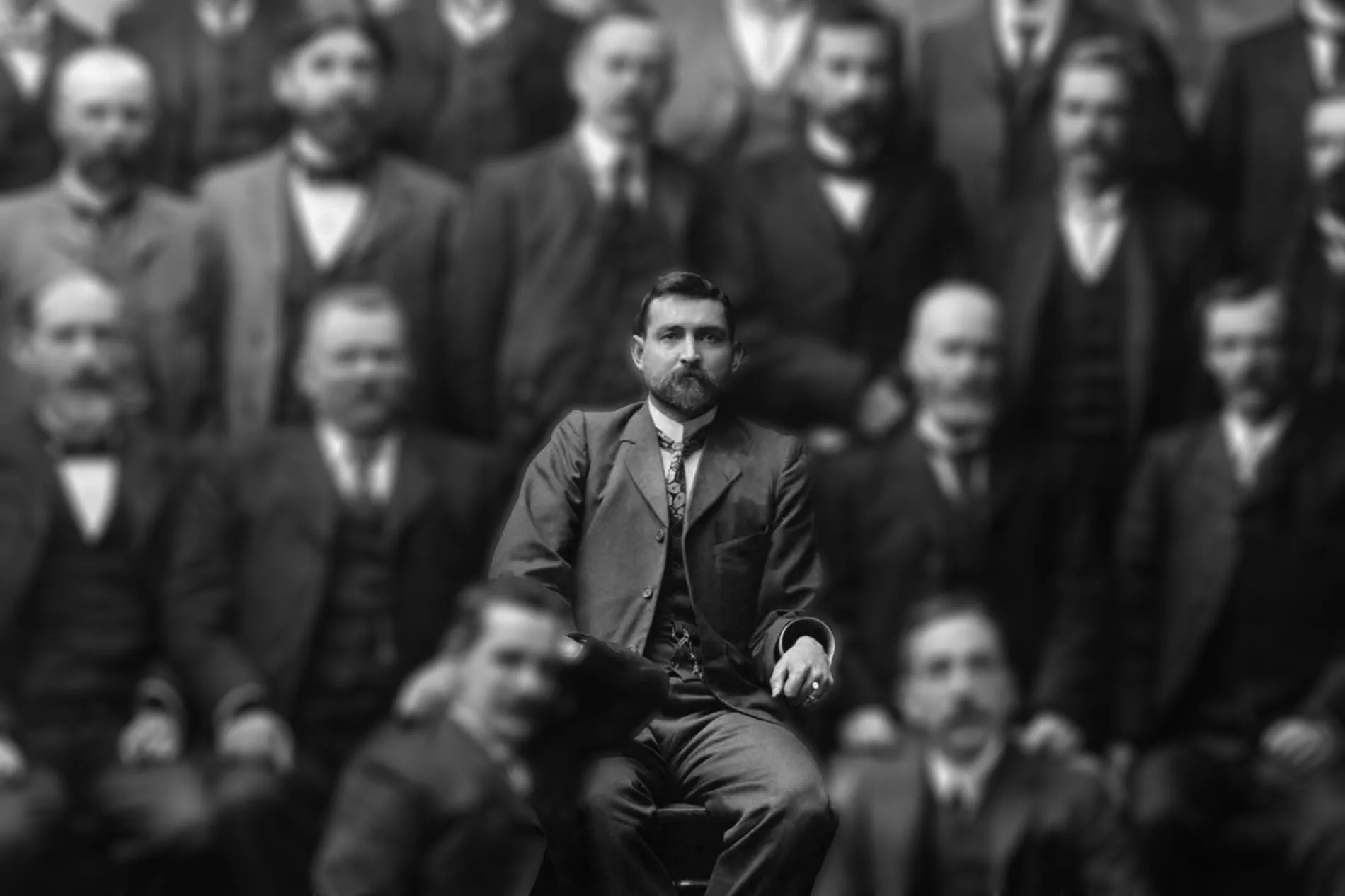

A perfect picture of the statesman: John Christian Watson

- DateTue, 30 Apr 2013

A notable date, 27 April, marks the anniversary of the Watson government.

On 27 April 1904, the government of Alfred Deakin collapsed after Labour members led by John Christian Watson withdrew support. Watson was then commissioned to form a government, which lasted just four months.

It was notable for two reasons: first, because Labour was the first socialist or social democratic party to come to power in any national government (Britain would not get a Labour government until 1924). Secondly, Watson was not a British subject and thus was legally ineligible to be a Member of Parliament. Of course, nobody knew that at the time!

Watson was born as John Christian Tanck in Valparaiso, Chile, in 1867. His father, Johann Tanck, was a Chilean of German descent and his mother, Martha Minchin, was a New Zealander and after Johann and Martha separated, Chris (as he came to be known) was educated in New Zealand. It was there that Martha married George Watson, a miner and quarryman. Chris took Watson's name and always maintained that George Watson was his father.

In 1886, Watson moved to Sydney and it was there that he became involved with the trade union movement. In 1889, Watson married Ada Lowe. Nothing is known about her, and no photographs of her have ever been found.

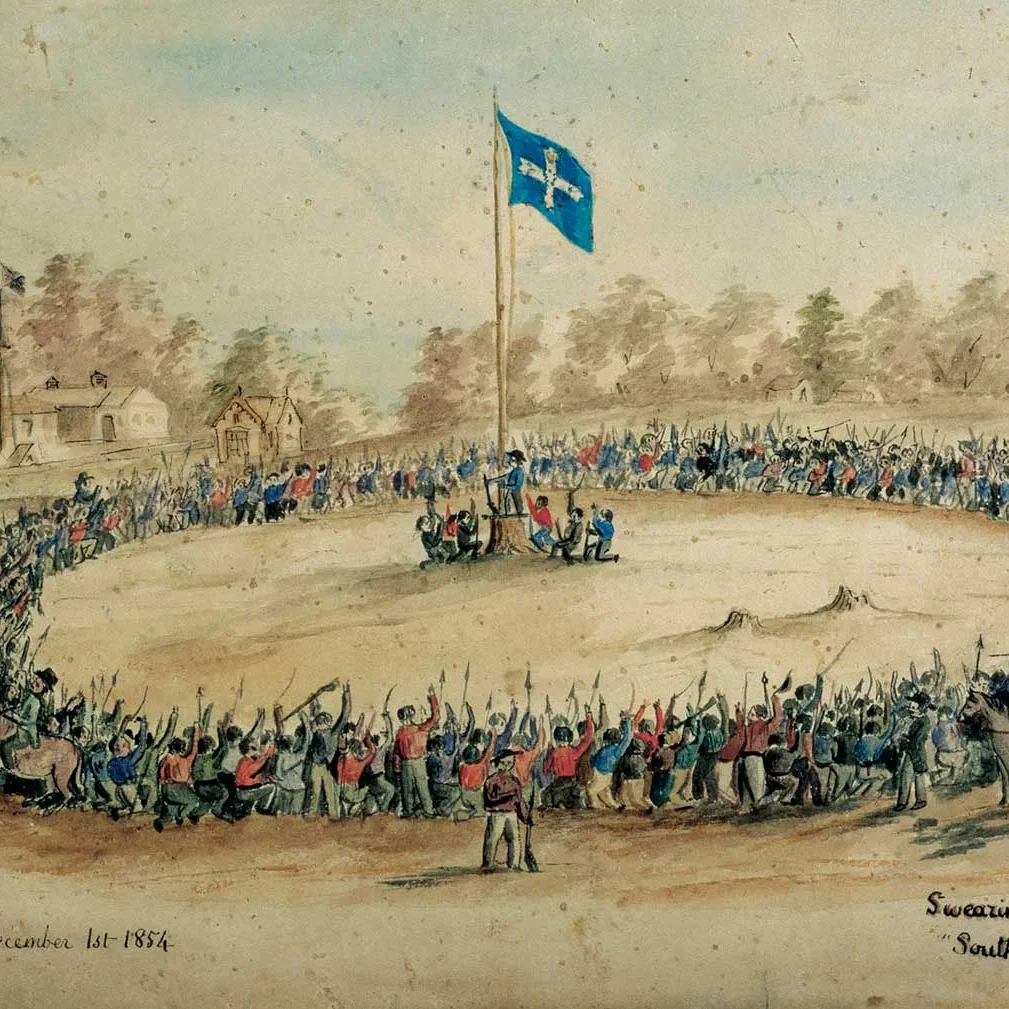

Watson was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in 1894, representing the electorate of Young. Charismatic and shrewd, Watson was a rising star of the Labour movement, and became a leader of the Labour members in the parliament. A strong negotiator, Watson was able to get concessions from the Free Trade premier, George Reid, and later helped fight for, and then against, the federation of the colonies. Though supporting Federation, Watson was opposed to the constitution as it was presented, believing the Senate would have too much power. The referendum in 1899 passed, and despite his objections, Watson agreed that 'the mandate of the majority will have to be obeyed'. In 1901, he was one of 14 Labour members elected to the first House of Representatives, representing the rural seat of Bland, based around Young and Wagga Wagga. There was no national Labour party at the time. The Labour members met on 8 May and agreed to establish a Federal Parliamentary Labour Party, the forerunner of the modern Australian Labor Party. Watson was chosen as the party's leader.

Watson continued his strategy of making deals and getting concessions in exchange for supporting the minority Protectionist governments of Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin. He and Deakin thought highly of one another and worked well together. But in 1903/04 they disagreed over the Conciliation and Arbitration Act, a framework for establishing Commonwealth workplace relations laws. Watson wanted the laws to cover state public servants, and when Deakin refused, Labour withdrew its support. Clearly, however, Deakin still respected Watson, because he advised Governor-General Lord Northcote to appoint Watson to form a government.

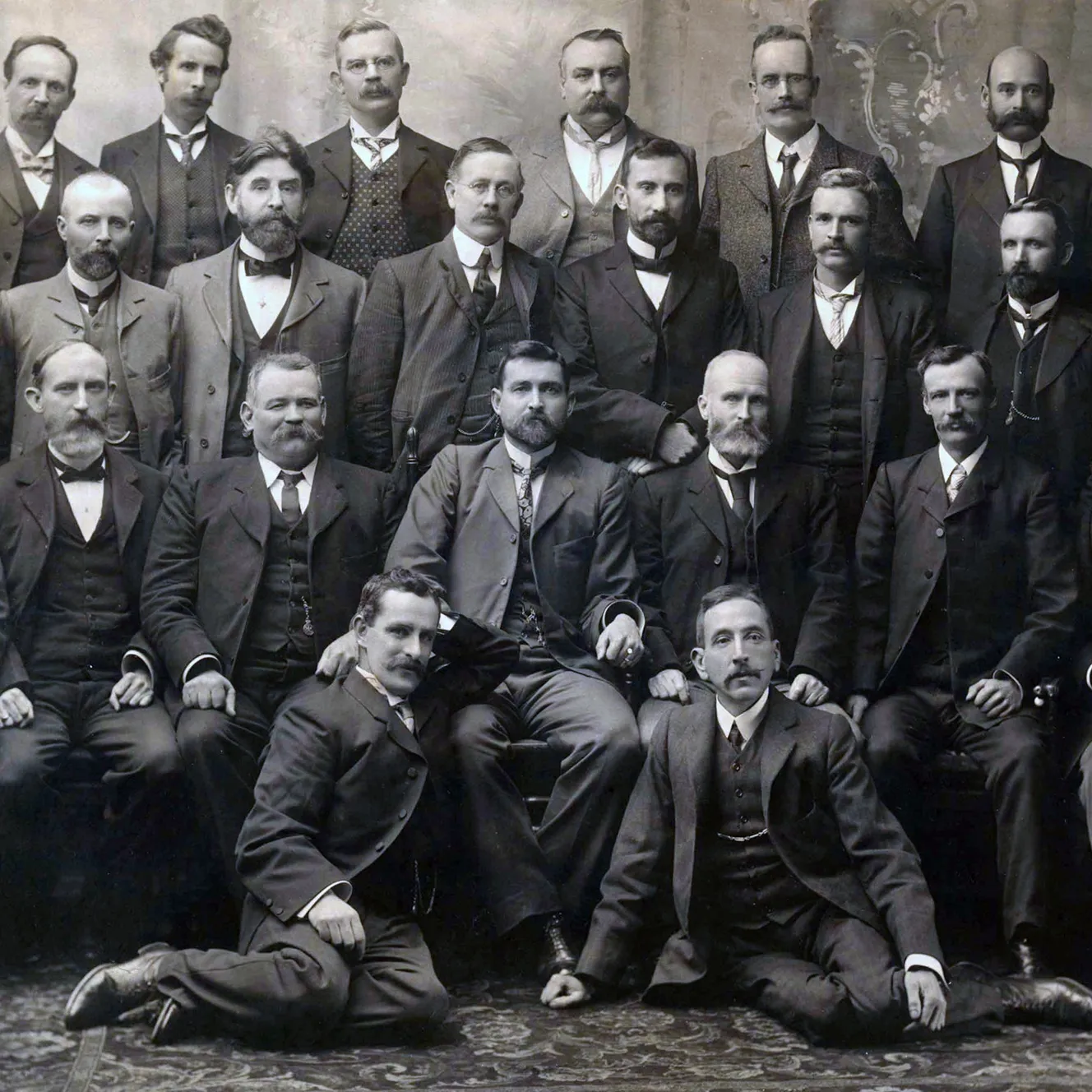

Aged just 37, Watson was and remains Australia's youngest prime minister. Billy Hughes, the External Affairs minister in Watson's brief administration, later reflected on Watson's first cabinet meeting.

'The new Prime Minister entered the room, and seated himself at the head of the table. All eyes were riveted on him; he was worth going miles to see. He had dressed for the part; his Vandyke beard was exquisitely groomed, his abundant brown hair smoothly brushed. His morning coat and vest, set off by dark striped trousers, beautifully creased and shyly revealing the kind of socks that young men dream about; and shoes to match. He was the perfect picture of the statesman, the leader.'

Watson's government was short-lived but eventful. The majority of legislative work was taken up with the same Arbitration and Conciliation Bill that had ended the Deakin government. Although he had an ambitious reform agenda, Watson simply did not have the numbers in the House of Representatives to govern effectively. In August 1904, Watson went to Lord Northcote and asked for a double dissolution of parliament. Northcote refused and instead appointed George Reid as prime minister, who later passed the Arbitration and Conciliation Bill, which did indeed extend its provisions to state public servants as Watson wanted.

Watson continued to lead the Labour Party in opposition, but in October 1907 he resigned the leadership, and retired from parliament in 1910. He devoted most of his life to business, but continued to be active in politics for more than a decade. He fell out with the ALP over the conscription issue and, alongside Hughes, was expelled for supporting sending conscripts to fight in the First World War. His biggest achievement after leaving politics was his chairmanship of the National Roads and Motorists Association (NRMA) which he helped found.

Watson's first wife Ada died in 1921. In 1925 he remarried Antonia Dowling, a 23-year-old waitress whom he met when she served his table at a Sydney club. Watson died in his home at Double Bay in 1941.