Australia’s entry into the Second World War

- DateMon, 02 Feb 2009

As Australia went onto a war footing, the Australian Parliament readied itself for action.

‘Strained relations exist with Germany. … Take necessary action in accordance with Commonwealth and Departmental War Books’, the Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department wrote to the Clerks of the Houses on 2 September 1939. A day later Robert Menzies sadly announced that we were at war, broadcasting from the Commonwealth Offices in Melbourne:

‘It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that, in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.’ ‘We can be a saddened but determined people in this crisis…there was no alternative but for this dreadful affliction to come to mankind,’ reflected Opposition Leader John Curtin on the 7th of September.

Australia’s parliamentary democracy survived and grew during the Second World War. This was partly due to these two great parliamentarians, both of whom served as Prime Minister in the long war that followed.

Menzies and Curtin were very different from each other. They had been on opposite sides of politics in the First World War: they still were. They handled their difficult job differently, had different ideas about how to respond politically to Australia’s greatest crisis, and had different political fates. Menzies lost the support of his own party and resigned dramatically, here at what was then known as the Provisional Parliament House. His successor was overthrown in the House of Representatives, and Curtin took over. He died in office in 1945: Menzies returned to power in 1949 and governed for the next sixteen years.

But what Menzies, Curtin and their parliamentary colleagues shared was more important than what divided them. They believed that the defence of Australia transcended political differences. They honoured Australia’s traditions of parliamentary democracy, at a time when democracy was under threat everywhere in the world, and sat together in Menzies’ unique experiment, the Advisory War Council, for much of the war.

The Advisory War Council was established following the September 1940 general election at which the Menzies government retained power only through the support of two independents. As a consequence, Menzies invited the Labor opposition leader, John Curtin, to join a national government. Curtin declined, instead suggesting a War Council be formed consisting of members of both the government and opposition. Menzies agreed, and the Advisory War Council was formed, meeting for the first time on 29 October 1940. The Advisory War Council was chaired by the Prime Minister and included members of the War Cabinet and the Leader and three members of the Opposition. If decisions of the Advisory War Council were unanimous, they had the strength of Cabinet decisions – a unique experiment in bringing the Opposition into the process of governing. Responsibilities of the Advisory War Council (and the War Cabinet) included military strategy, armaments and munitions, aircraft production, transport, and railways.

Menzies and Curtin fought each other with words on the floor of the House, in hotly contested elections and referenda – one election a draw, the other a landslide win – but accepted the results. Their governments gained enormous power over the Australian people and economy, but did so according to the Constitution.

One item in the Museum’s collection particularly recalls the tangled international politics of the war years and Australia’s role as a key part of the alliance that stood against the Nazi terror. This rare printed item, the Longfellow broadsheet of 1941, was printed at the command of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill as a keepsake of his and President Franklin Roosevelt’s dramatic secret meeting off the coast of Newfoundland in August 1941. Roosevelt had earlier scribbled the verse as a personal message of support to Churchill in early 1941, when American entry into the war seemed remote. Churchill had it printed, and both he and Roosevelt signed a few copies on the last day of their meeting at sea in August 1941. At their meeting Churchill and Roosevelt drafted the Atlantic Charter, the agreement on war aims which was to be the basis of the enduring Anglo-American alliance. An image of the Longfellow broadsheet can be seen at our website about Menzies’ 1941 war-time diary.

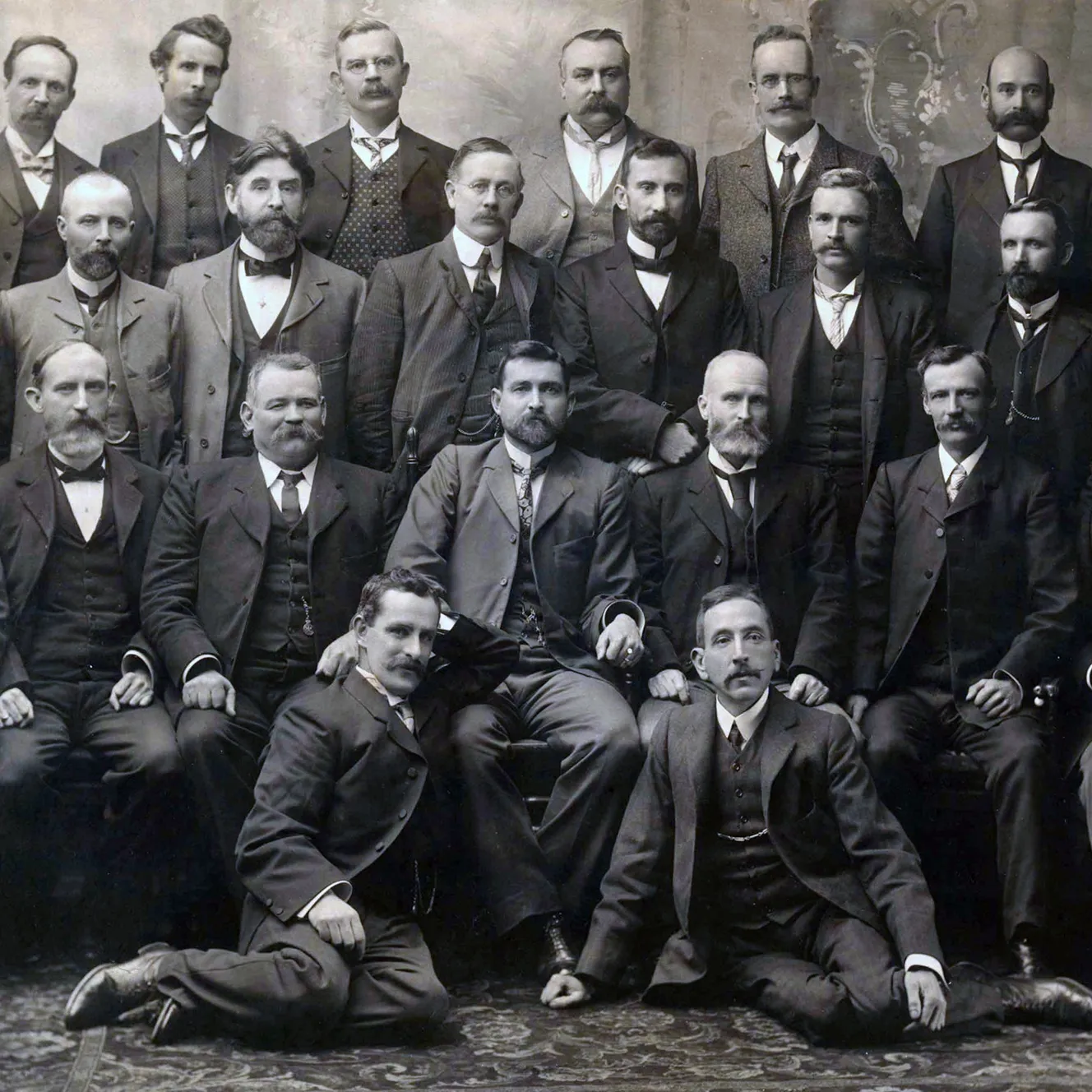

The image above shows six prime ministers in the Advisory War Council in 1940. Five of the men surrounding Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies (1939-41, 1949-66) once also held the title of prime minister. They are (third from left) Francis Forde (1945); (fourth from left) John Curtin (1941-45); (fourth from right) William Morris Hughes (1915-23); (second from right) Arthur Fadden (1941); and (right) Harold Holt (1966-67).