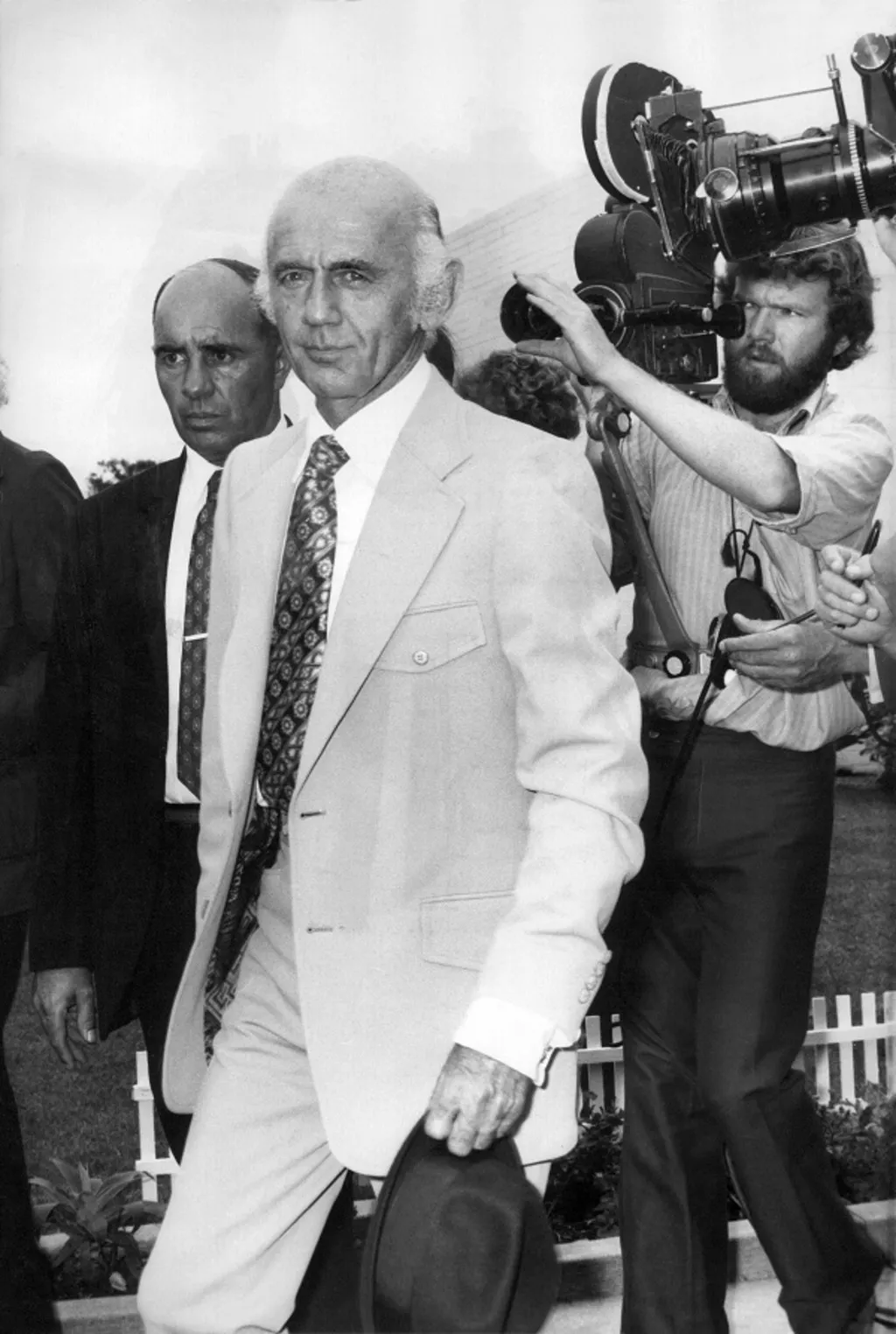

When William McMahon became Prime Minister

- DateThu, 10 Mar 2016

He had been around for a long time. He knew what was significant and what was not.

The stories about the cessation of civic aid to the South Vietnamese? The ructions between the Defence minister and his department?

It was ‘a little conflict of no consequence,’ William McMahon told a colleague.

He was wrong. The consequences of that little conflict would be huge.

Within a week, that Defence minister would resign and launch a stinging attack on John Gorton, Australia’s prime minister since 1968. Gorton himself would step down in the wake of a tied ballot of confidence, and McMahon—long-thwarted yet always persistent—would unexpectedly ascend to the office he’d hoped for so long to attain: the prime ministership.

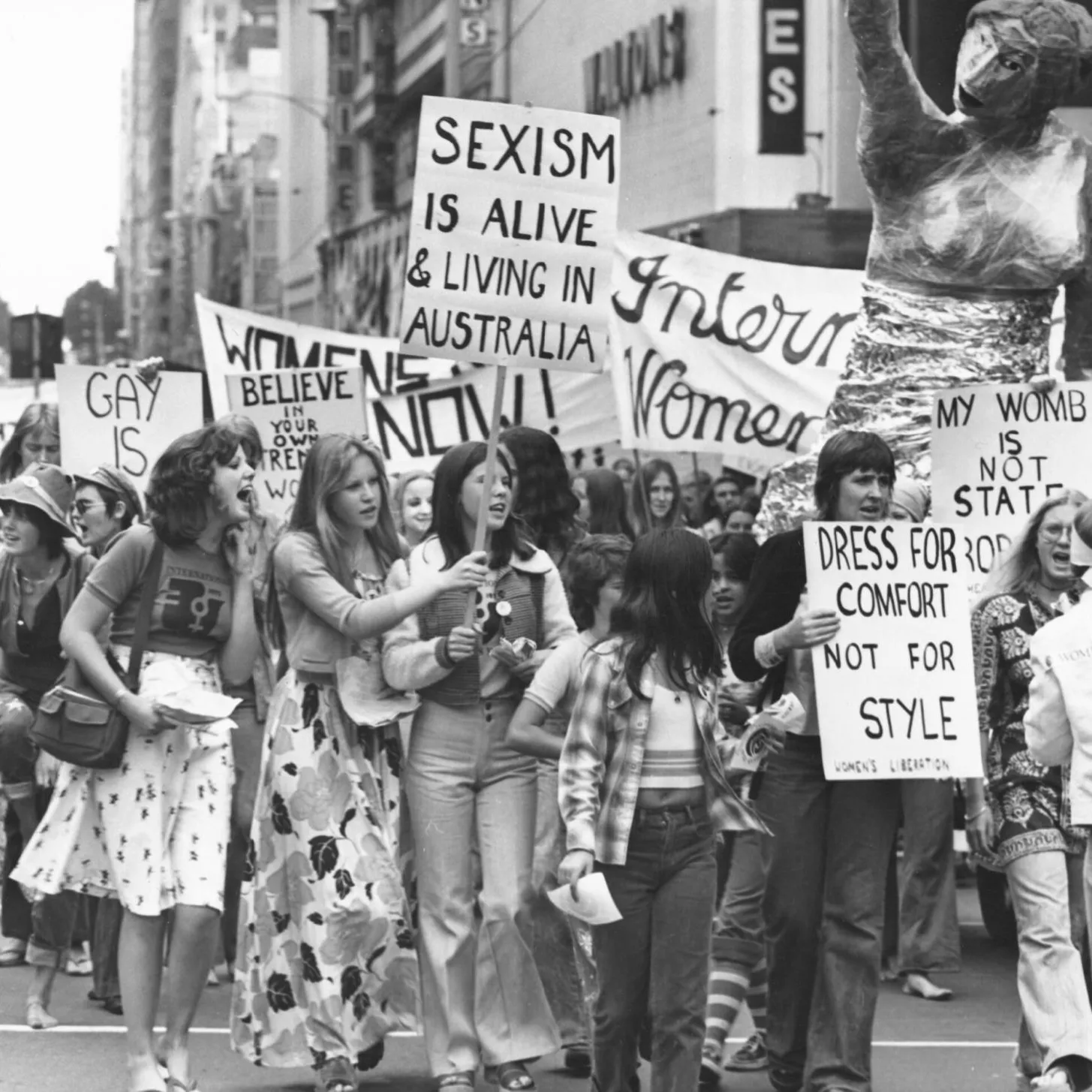

The tenth of March marks the anniversary of when McMahon became Prime Minister, and with each year that passes his time in office seems like his dismissal of the crisis that brought him to power: a little thing of no consequence. Only twenty-one months long, the popular reputation of the McMahon Government is derisory, and memory of the man himself has been flattened into a caricature by the writings of so many journalists and colleagues.

That McMahon is remembered most for his short prime ministership is understandable, yet this narrow focus does occlude knowledge of an otherwise long and successful political career that began with the election of the Menzies Government in 1949.

Made a minister two years after his entry into the Parliament, William McMahon was a jack-of-all-trades for almost two decades, serving across the ministry in portfolios for the Air, the Navy, for Social Services, Primary Industry and Labour and National Service.

By the time of Menzies’ retirement, McMahon had established himself as a capable administrator and a safe pair of hands.

He was made Treasurer and deputy party leader to Harold Holt; he was Minister for External Affairs—renamed Foreign Affairs at his insistence—to John Gorton.

By the time McMahon became prime minister, he had served a long and wide-ranging apprenticeship.

Yet he had also aroused great dislike.

A reputation for leaking to the press had provoked widespread contempt amongst his colleagues; McMahon’s presumption to speak down to them had endeared him to few; his attention to fashion was thought vain and superfluous.

In a pen portrait that was posthumously published, Paul Hasluck described McMahon as ‘disloyal, devious, dishonest, untrustworthy, petty, cowardly’.

John McEwen, the leader of the Country Party, had such a scathing dislike for McMahon that he intervened to prevent him becoming prime minister in the wake of Harold Holt’s disappearance and death: ‘Bill,’ McEwen said to McMahon, ‘I will not serve under you because I don’t trust you.’

The antipathy between them echoed the divisions between the Victorian and New South Wales state Liberal Party branches.

Coming from a wealthy Sydney family, McMahon had absorbed his state’s liberal outlook on trade and economics, and reinforced it with a degree in economics from the University of Sydney.

This was in stark contrast to the more interventionist values held in Victoria—values that were deeply felt: ‘Never let the prime ministership fall into vulgar, Sydney commercial hands,’ Sir Alexander Downer told one Victorian MP.

McMahon’s triumph in spite of such attitudes and divisions underscores both his resilience and persistence.

He had used his connections in the media to help make his reputation, and he had coupled a considerable work ethic with political nous in order to survive and get ahead.

After McEwen’s intervention against him in 1967, McMahon had held his fire in order to maintain his position as Treasurer and deputy leader of the Liberal Party.

After the 1969 election, when the government suffered a 7% swing and lost seventeen seats, McMahon stood for the leadership but was beaten again.

It was a way of keeping himself in the frame, and many viewed his subsequent move into External Affairs as Gorton’s attempt to get rid of him.

Yet McMahon could not be denied.

On 3 March 1971, stories about the withdrawal of civic aid to the South Vietnamese – the little conflict that McMahon dismissed – prompted accusations of disloyalty and betrayal between John Gorton and his minister for Defence, Malcolm Fraser.

Already discomfited by Gorton’s apparent willingness to exercise authority unilaterally, Fraser resigned a week later and attacked the prime minister in a bitter speech to the parliament: ‘I do not believe he is fit to hold the great office of Prime Minister, and I cannot serve in his government.’

Fraser’s actions put the fire to the fuse.

Discontent with John Gorton’s leadership had been intensifying since that 1969 election, and his apparently curt methods of dealing with his ministers had provoked antipathy.

His backers, seeking to assert the prime minister’s authority, moved a ballot of confidence in his leadership in a subsequent party room meeting. It was a tactical mistake compounded by a decision to allow a secret ballot instead of a show of hands.

Gorton was stunned at the outcome: thirty-three to thirty-three. A tie.

Whether he could exercise a casting vote has been debated ever since, but the upshot was Gorton’s resignation.

Suddenly, the party’s leadership was vacant.

The prime ministership was up for grabs.

McMahon had been sitting in a large green armchair with his hand capped over his forehead and eyes, ‘affecting an indifference to what was transpiring,’ Jim Killen later wrote.

Indifferent or not, the prize he had strained for so long to attain was within reach.

Gorton asked him, ‘Will you stand, Billy?’

Yes, McMahon replied.

Malcolm Fraser, taking a seat by the Victorian MP Neil Brown, lit his pipe and told Brown that McMahon was the only choice for the leadership.

Who else could be appropriate, after all?

McMahon was one of the last of the Menzies men. He had the most ministerial experience of all the MPs assembled in the party room. He had proved himself competent in his portfolios. He had been there for a long time.

Who else could it be?

Gorton’s resignation and McMahon’s election over Billy Snedden was announced to the press waiting in King’s Hall.

At a subsequent press conference, the new prime minister sat with his wife by his side and declared that he had seen Prime Ministers come and go. He’d seen the ministry change many times over.

‘[…] I don’t feel the slightest bit excited or emotional’, McMahon told the press. ‘I’ve taken it in a composed way because I have been here for a long time.’

Twenty years of experience lay behind him. A year and a half in which to use it lay before him.