A fascist sex symbol?

- DateWed, 12 Dec 2012

These items in the Museum's collection dig deeper into one of the more famous stories in Australian history.

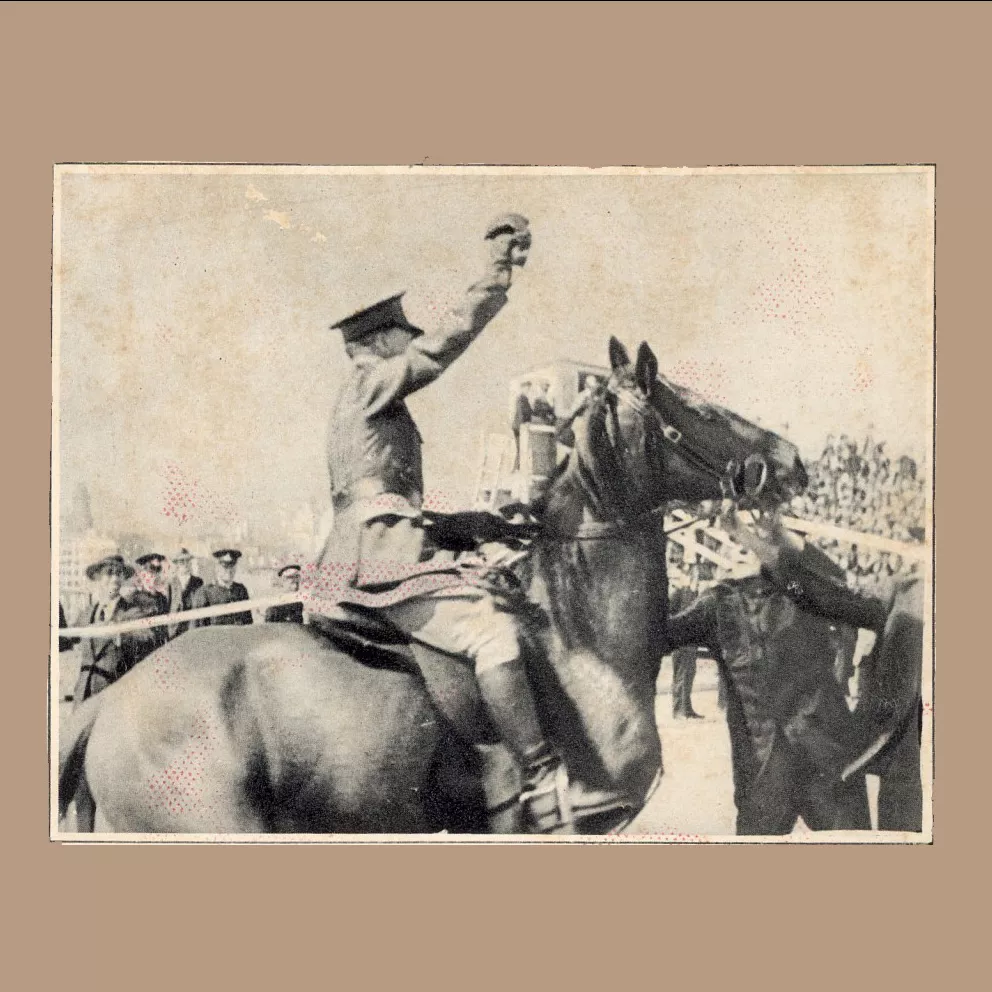

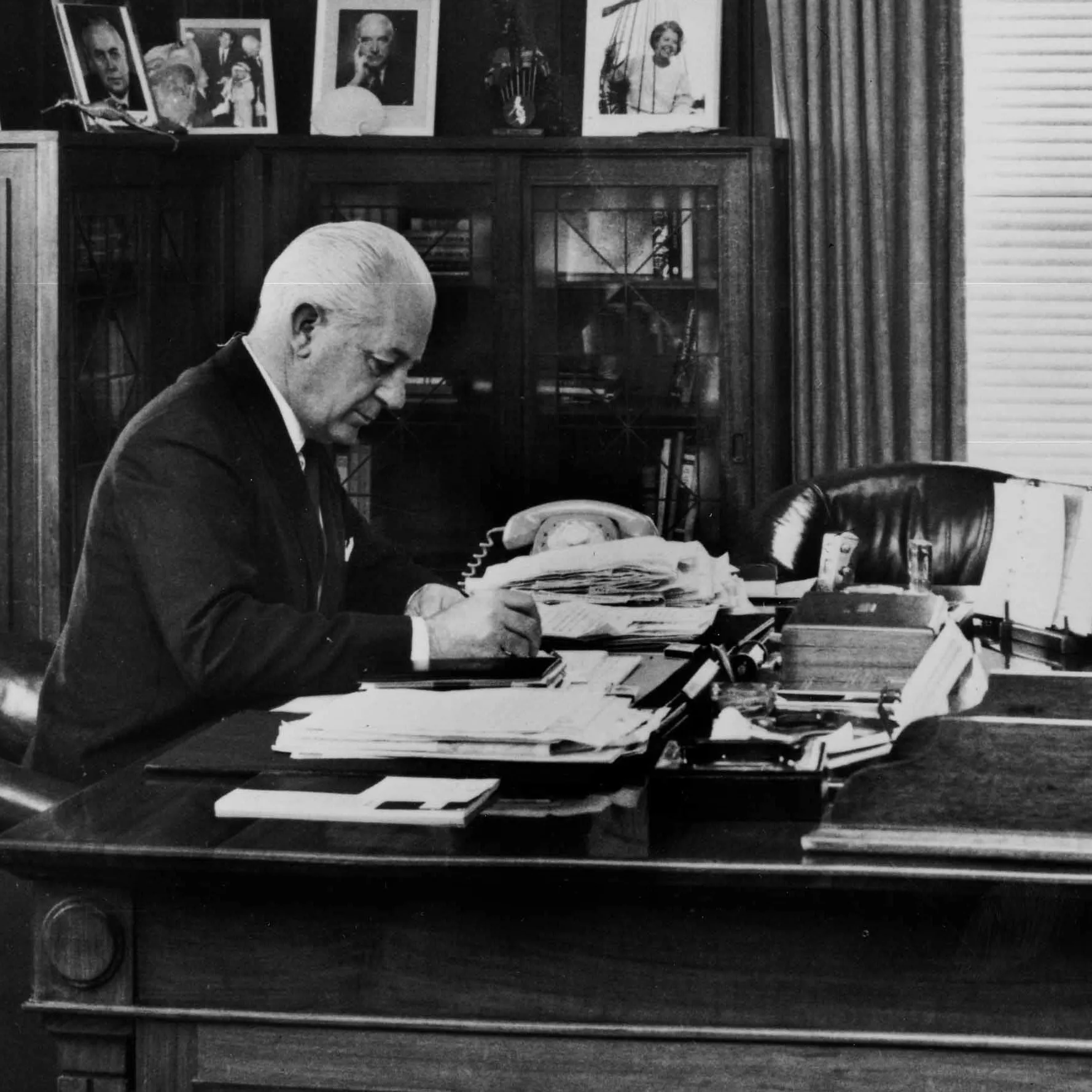

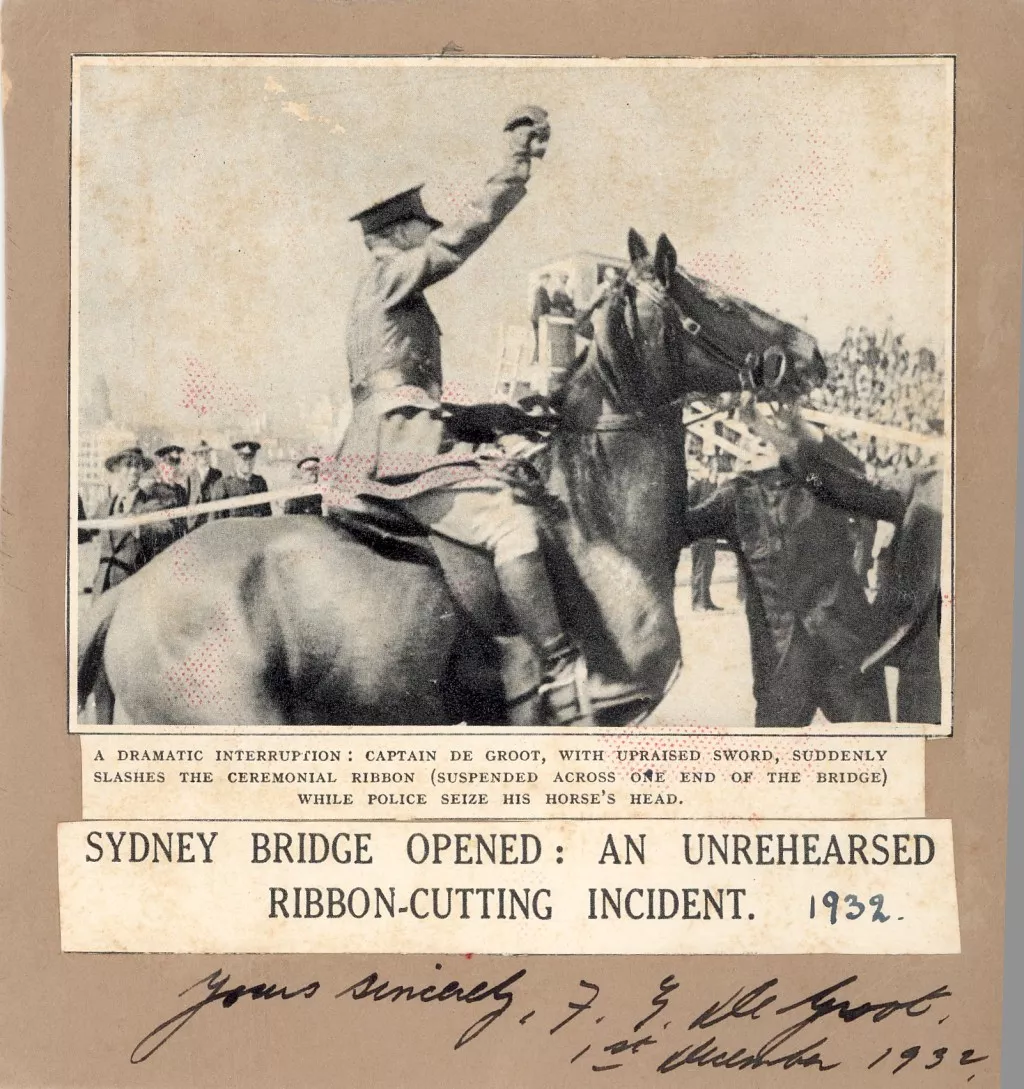

On 19 March 1932, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was opened by Premier Jack Lang. The cutting of the ribbon, though, was performed before him by Francis De Groot, a member of the paramilitary New Guard. He rode up on a horse, dressed in full military uniform and declared the bridge open ‘in the name of the decent and respectable people of New South Wales.’ The incident embarrassed Lang, but was a symptom of the deep divisions in New South Wales (and Australia as a whole) during the Great Depression. The New Guard was bitterly opposed to Lang and his Labor government, which they saw as a communist threat. De Groot was arrested but acquitted on the basis that none of his acts were illegal, although he was fined for trespassing.

Francis De Groot rides up on a horse, dressed in full military uniform and declares the bridge open.

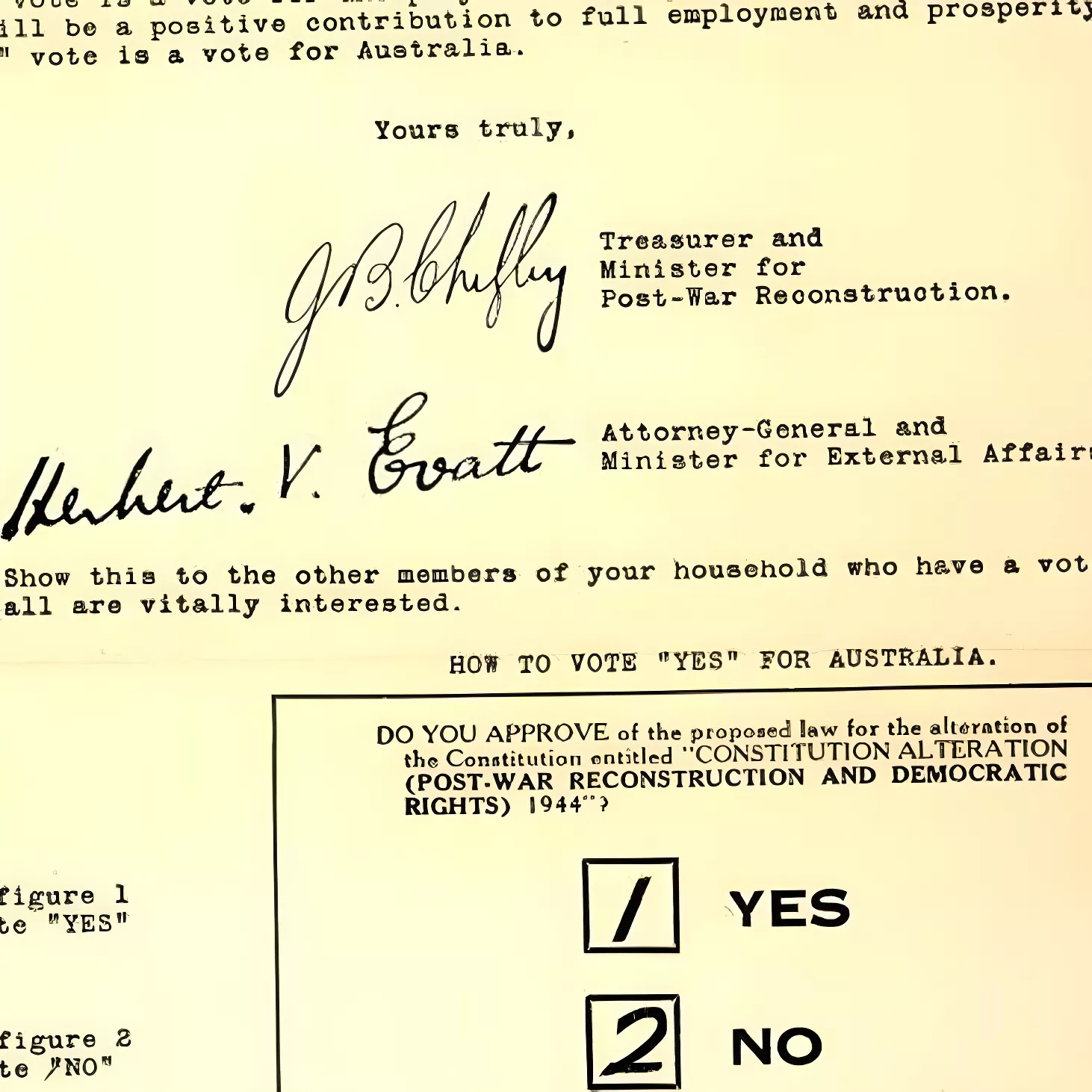

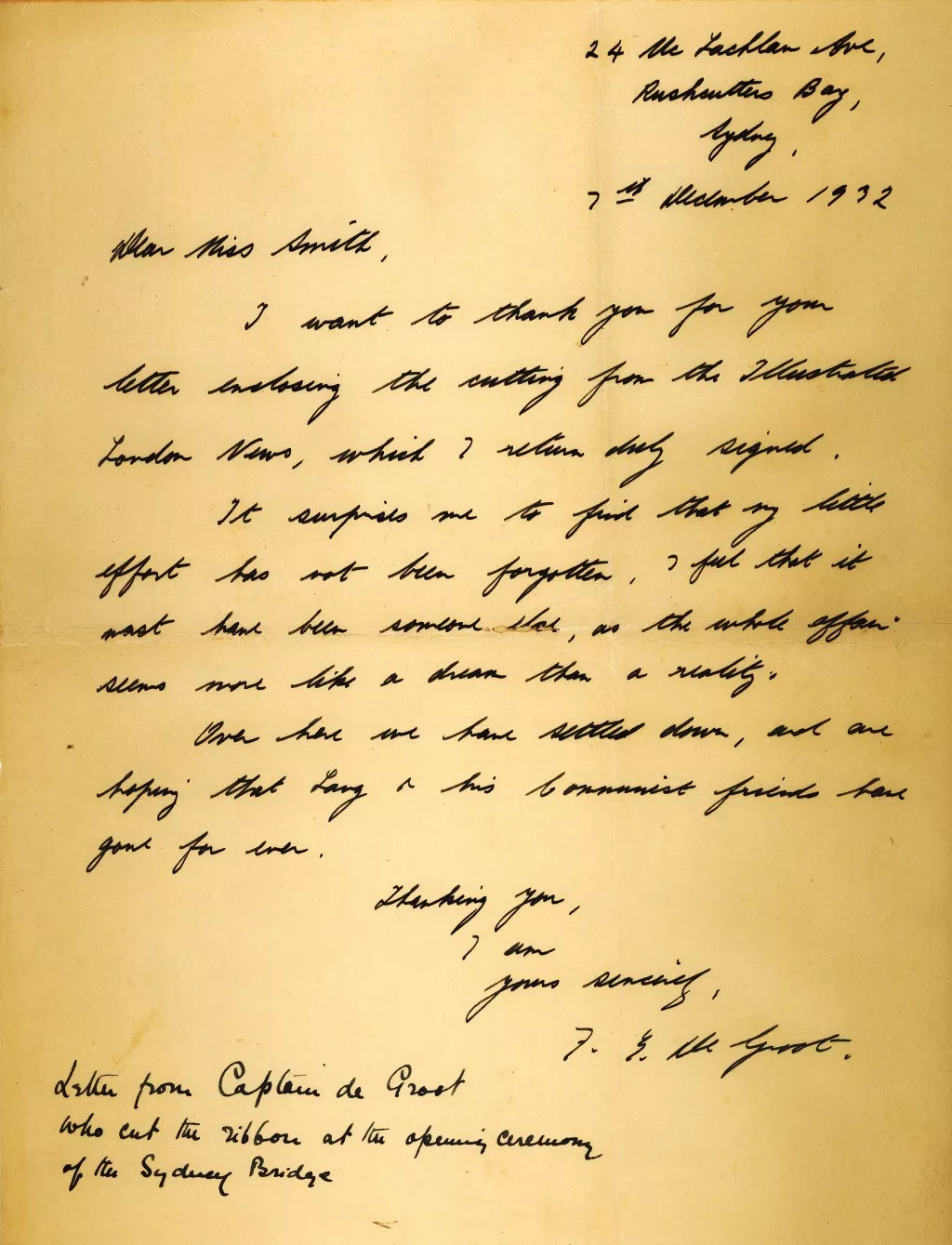

De Groot became a celebrity after the incident, with publicity for his actions reaching as far as his native Ireland. To many, De Groot was just a madman who intruded in a public ceremony and stole the Premier’s thunder for his own ends. To those who sympathised with the New Guard and opposed Jack Lang’s government, De Groot was a hero. Subsequently he was interviewed by the press and engaged as a public speaker. He also received hundreds, if not thousands, of letters from admirers and well-wishers. One such piece of fan mail was this photo of De Groot’s famous deed from the Illustrated London News, which an admirer from the UK had sent him and asked him to sign. Not only did he oblige, but he sent this hand-written letter in response thanking her and admitting some humility over the incident.

Letter from Captain de Groot who cut the ribbon at the opening ceremony of the Sydney Bridge.

Andrew Moore, in his book about De Groot, says the Harbour Bridge incident made De Groot a sex symbol. A surprising number of De Groot’s new fan club was female. Whether or not it was the sex appeal of a man in uniform, the phallic imagery of his deed, or that Frank’s diminutive proportions had encouraged the maternal instincts, remains to be seen. Nonetheless, as Miss Alana Malross of Bondi wrote: 'Women ever admire bravery and strength in a man (be it mental, moral or physical) and I surmise Captain De Groot’s action has earned for him many female admirers.'

The newfound celebrity of one of its members even encouraged the New Guard to recruit women into the organisation and De Groot himself launched a Women’s Auxiliary for the paramilitary group. The New Guard obviously thought that the prospect of meeting their brave, dashing hero would be enough to attract women to their cause. And he was seen as a hero; to some, De Groot had struck a blow for liberty and against communism by his actions. One fan wrote to De Groot’s wife, Bessie, to say that his effort ‘was as audacious as any that Wellington or Nelson could have conceived. We think his name ought to hold an honoured position in Australian history side by side with Wentworth, Lawson, Blaxland and other great Anglo-Australians’.

This unique letter and photograph shows the level of support and admiration De Groot earned from those who opposed the Lang government and is a fascinating glimpse into the personality and life of Francis De Groot, who must surely now be considered Australia’s first and possibly only fascist sex symbol.