Young people and the right to vote: Some exceptions to the rule

- DateThu, 16 Mar 2017

On 16 March 1973 the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1973 gave all Australians aged 18 years or older the right to vote. The first federal election at which all 18-year-olds could vote was held in May 1974.

But the 1974 election was not the first to draw teenagers to the ballot booths. There had been earlier opportunities for young people to vote alongside their older counterparts.

Fight for your right

The original Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 and its predecessor, the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902, permitted only people aged 21 years and over to vote. Voters had to be non-Indigenous, although there were some exceptions. But in the years that followed, world events forced some deviations from the rule. It seems that if you were old enough to fight for your country, you had earned the full rights of citizenship – and you were old enough to vote.

Indeed, some parliamentarians suggested lowering the voting age before the 1918 legislation was even passed. In 1917, during the First World War, Labor member for Brisbane William Finlayson proposed that all members of the armed forces aged 18 years should be enfranchised. The proposal was rejected, but the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 did allow for all current and former defence force personnel to vote at federal elections during the war and for three years after the end of hostilities. No minimum age was specified, so it’s possible that 20,000 to 30,000 young people – even people younger than 18 – were suddenly able to vote.

During the Second World War, active and discharged defence force personnel under 21 years of age again qualified to vote, thanks to the Commonwealth Electoral (War-time) Act 1943 introduced by John Curtin’s Labor government. But there was a catch: the vote was restricted to young non-Indigenous people who were serving or had served overseas.

Voting rights for Indigenous Australians

Further reforms came after the war, when the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1949 granted Indigenous defence force personnel the right to vote in federal elections. (It also granted this right to Indigenous Australians who already had the right to vote in their state or territory elections.) The vote wasn’t granted to every Indigenous Australian until 1962.

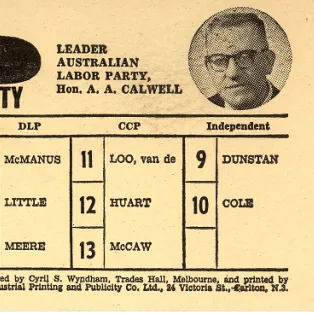

Further changes came in the midst of yet another armed conflict, the Vietnam War. In 1965 the Labor Opposition moved to amend the Commonwealth Electoral Bill (No. 2). If young people could work, pay taxes and get married, the Opposition argued, then young people should be entitled to vote for the government that created the laws (and enforced the taxes) they were obliged to obey. The matter was even more pressing given that conscription had been introduced in 1964. Those who were eligible to be called up, the Opposition said, should have the right to decide on the government that did the calling.

However, the Menzies government disagreed that the franchise should be extended to all people 18 years and over. It is possible (as some Opposition members argued) that the reform wasn’t made because younger people may have been more likely to vote against a conservative government. But the Holt (Coalition) government did amend the Act in 1966 to enfranchise service personnel who were or had been on active service overseas, or had served within the Far East Strategic Reserve. Young National Servicemen who had not served in Vietnam did not get the vote.

Missing in action

Some forty years on, indications suggest that young people are increasingly disaffected with the electoral system. At least, everyone from opinion pollsters and academics to journalists and politicians seems to be saying so. The Australian Electoral Commission reported that just 51 per cent of 18-year-olds and 76 per cent of 19-year-olds were enrolled to vote in early 2016. But by the time enrolments closed on 23 May 2016, in the lead-up to the 2 July 2016 federal election, 71 per cent of 18-year-olds and almost 84 per cent of 19-year-olds were on the electoral roll.

Maybe young people are not so disaffected after all. However, as of December 2017 some 12 per cent of eligible people in the 18- to 24-year-old age group were still missing from the electoral roll. This percentage of missing voters is higher than that of any other age group in Australia.

Voting is both an action and an engine of democracy. Imagine what impact those missing voters could have on the outcome of an election!